World Congress

Sisters by Heart joined the global effort this August at the 8th World Congress of Pediatric Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery in Washington, D.C. Board Members Meg Didier and Lacie Patterson submitted an abstract and presented the poster titled, “Sisters by Heart: Empowering Patients and Families Affected by Single Ventricle Heart Disease (SVHD).”

This opportunity was due in part to our new partnership with Global ARCH which brings CHD organizations from around the world together in common purpose. Additionally, Meg gave two presentations at the conference; “The Journey” and “Organized Patient and Provider Collaboration” which provided the patient perspective to navigating life with SVHD as well as a basic structure for effective patient/provider collaboration in care.

Leadership Change

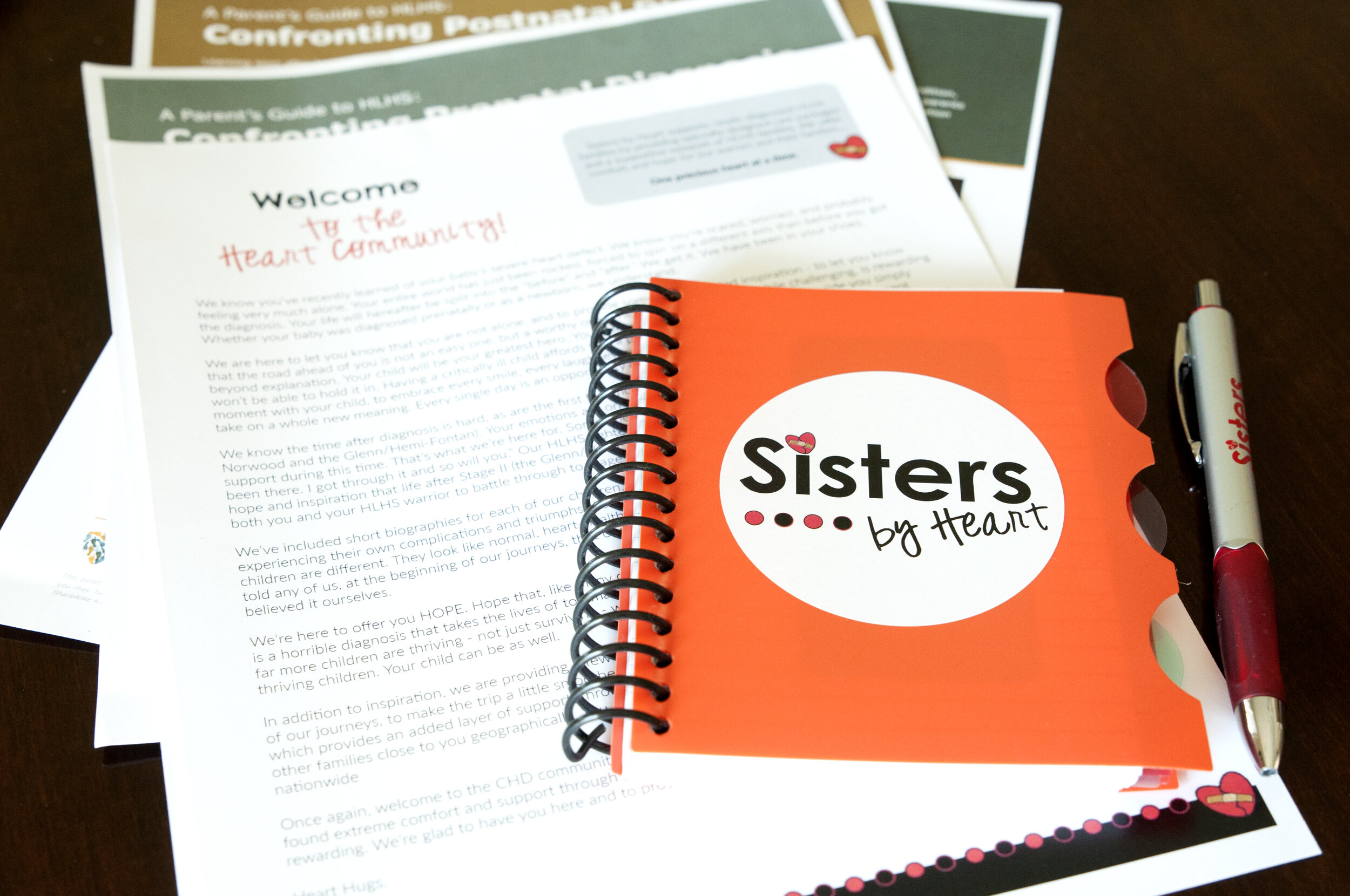

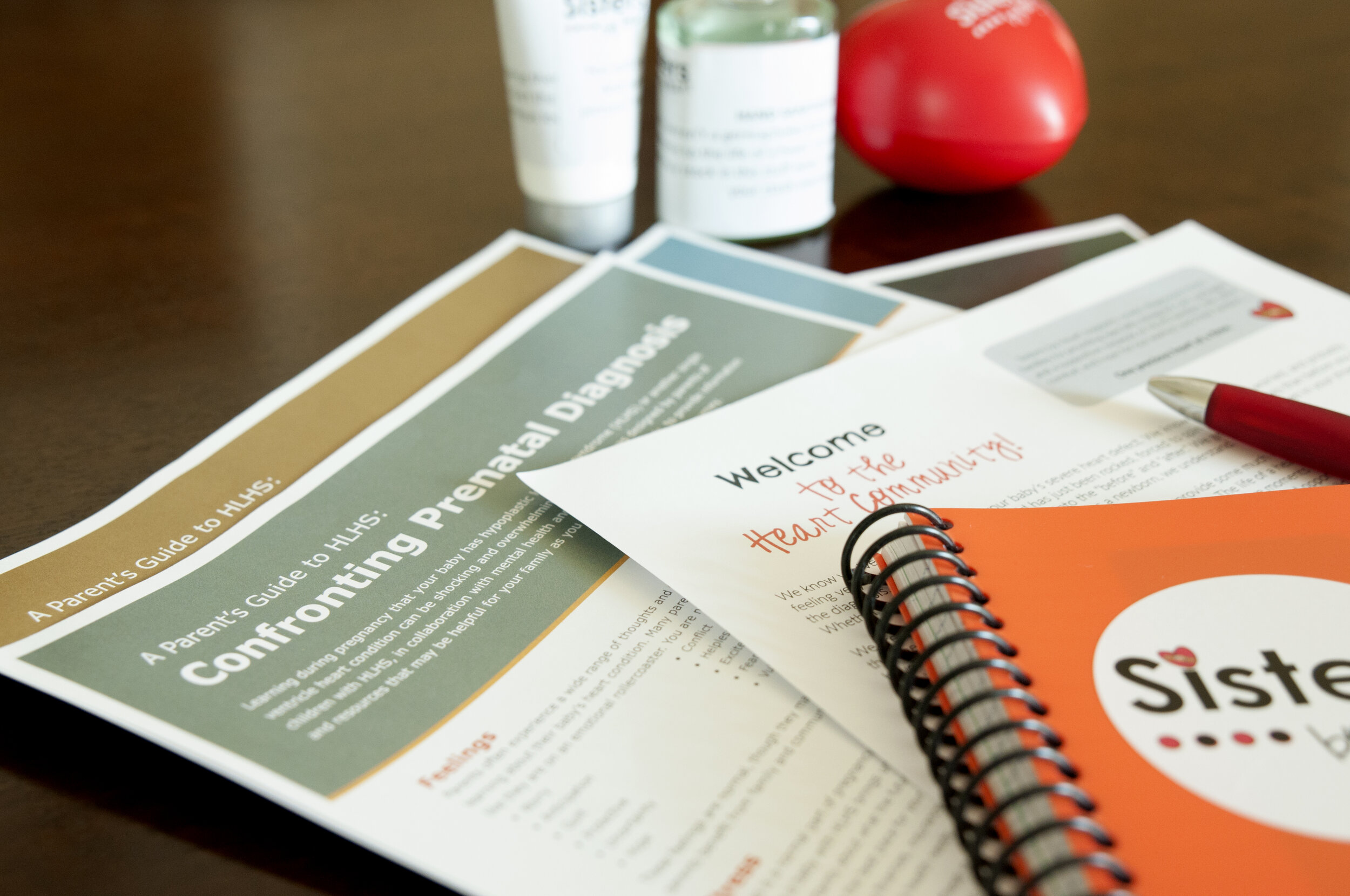

A little over twelve years ago, Sisters by Heart sent out its first care package. A few months later, we officially obtained our 501(c)(3) status and the incredible Stacey Lihn stepped into the formidable role as our founding President.

Stacey’s Legacy

Over the past decade, she has shaped our vision and dreamed bigger for ourselves than we ever could have imagined. Under her dedicated and tireless leadership, Sisters by Heart has expanded from reaching newly diagnosed parents facing an HLHS diagnosis, to entire families, children and adults living with not just HLHS, but all single ventricle defects. Along the way, we have developed partnerships with the National Pediatric Cardiology Quality Improvement Collaborative (NPC-QIC),

Looking Toward the Future

Lacie is passionate about empowering single ventricle families throughout their journey by relentlessly spreading a message of hope and by delivering support through education, collaboration and advocacy. We are excited to have Lacie’s leadership to further the mission of Sisters by Heart!

the Fontan Outcomes Network (FON), and the HLHS Consortium. We have become the preeminent resource of support for newly diagnosed single ventricle families and strive to continue that support throughout the journey. None of this would have been possible without Stacey Lihn’s leadership, and we are profoundly grateful for the more than a decade she dedicated to leading our organization.

Passing the Torch

As Sisters by Heart continues to grow and evolve, we are pleased to announce our new President, Lacie Patterson. Many in our community know Lacie well as she has been actively involved as a parent partner with NPC-QIC since 2016. She has served as both co-lead and executive sponsor of the dynamic group that created the Tube Weaning Toolkit for centers, and has been part of the NPC-QIC leadership team since 2018. In 2019, Lacie joined the Sisters by Heart Board of Directors in a role that supports our Fontan Families. In addition to her activities on a national level, Lacie has also been active in her local heart communities, serving on hospital patient and family advisory boards and focus groups.

Linking Hearts

Introducing, Linking Hearts! A one-to-one matching program open to all Sisters by Heart adult patients and parents to enhance community, connection, and support

About:

As the Sisters by Heart family continues to grow and provide support to all those in the single ventricle community, we recognize the desire of many to have closer and more personal connections to people who share their experiences. Sisters by Heart is committed to supporting single-ventricle patients and families from diagnosis, through treatment, and beyond. We heard your feedback and are thrilled to introduce: Linking Hearts, an extension of Linked by Heart, to provide one-to-one connections and support.

Linking Hearts is a matching program that connects members of the Sisters by Heart Community based on shared characteristics and experiences. The program helps adult patients and families make personal connections with others who live in the same area or share the same single ventricle diagnosis, or are in a similar place along the single ventricle journey. The program is free to join and open to all parents and caregivers of single ventricle patients in the Sisters by Heart community, including angel moms and dads, as well as patients themselves, ages 18 and older.

How Does this Program Work?

Patients and families can register and sign up for Linking Hearts on our website. Once registered, we’ll ask you to provide some information about yourself and/or your single ventricle child and ask you to agree to our terms of engagement and privacy policy.

Once registered, we’ll match you with others based on four key details: your profile type (patient, parent, etc), age of you/your child, diagnosis, and geographic location. We’ll also provide you with a list of potential special interest areas that you can select, such as specific post-surgical complications, education, or mental health and resilience. The confidential and secure matching system will suggest matches based on the shared criteria, and you can choose who you would like to connect with -- it’s that easy!

Once you choose who you’d like to connect with, they will be notified to ask if it’s a good time to connect. If they say yes, we connect you together and then leave it up to you to decide how and when you’d like to connect. Phone, email, or text -- whatever works best for you and your match!

FAQs

Pre-program launch:

Q. Who can join Linking Hearts?

A. Linking Hearts is currently open to all parents and caregivers of single ventricle patients in the United States, including angel moms, dads, and caregivers. Linking Hearts is also currently available to patients ages 18 and older.

Q: How do I sign up to be a part of Linking Hearts?

A: We are currently recruiting Linking Heart members to build up our matching pool and ensure we can make the most helpful matches possible. In order to join the matching pool, you will need to register and create an account. To do this, you will need to create a username and password and tell us if you are a parent/caregiver, an angel parent/caregiver, or an adult patient. Then you will enter some information about yourself and/or your single ventricle patient, including: the patient’s age, diagnosis, and geographic location. These 4 criteria will be used to generate your matches. You will also have a list of topics that you can select as areas of special interest such as education, post-surgical outcomes, or mental health and resilience. You will also have the ability to upload a photo and write a short bio about yourself, your family, and what you’re looking to gain from this program, which will only be viewable to other members once you’ve accepted their match.

Q. How will I be matched with others

A. We want to ensure your matches are the most customized to you and your profile. This may take some time as we recruit more Linked by Heart members to join our program. Once you’ve completed registering your account and filling out your profile, we’ll notify you when we are ready to begin matching!

When you’ve been notified of your matches, log back into the site and you will see the names, photos, and profile information of your matches. You will be able to review these profiles and choose who you would like to connect with and you’ll click a “Connect” button. The program will then reach out to those individuals to ask if they would like to be connected. If they say yes, the program will notify you. You can come back to the matching page again at any time to search for new matches. You can also update your matching criteria and special interest areas at any time to update your matches.

Q: When will I be matched with others?

A: We want to make sure the matches suggested to you are a great fit for you! As we are ramping up the Linking Hearts program and building our pool of potential matches, we are going to hold off on making any connections until we have enough potential matches. We’ll be sure to notify you when you’ve been matched, and you’ll be able to let us know if it’s still a good time for you. We anticipate the recruitment process may take a few months and we appreciate your patience!

Q: What information is shared with my matches?

A: The matching algorithm connects Sisters by Heart members based on 4 shared criteria: profile type (parent/patient), patient’s age, patient’s diagnosis, and general geographic location. Because this information is used in the matching process, it will be visible to potential matches within the Linking Hearts community. Your matches will also be able to see the special areas of interest you have identified. You have the option to add additional details, such as a photo and short bio, but these will only become visible to other members once you’ve agreed to connect with them as a match.

Q: How often do I need to connect with my match?

A: This program can be flexible to your schedule and needs; it is entirely up to you and your match how often you communicate. We recommend new matches review our Linking Hearts Community Agreements together to set some general agreements around frequency of communication, communication method, response times, etc. We want to make sure you and your match are set up for successful communication from the start! But we also want this to work for you and your match -- and we leave it to you to figure out what that looks like!

Q: What topics should my match and I talk about?

A: Again, this is entirely up to you and your match! When reviewing the Linking Hearts Community Agreements, you and your match can share topics that you are interested in discussing and learning more about. All we ask is that you don’t provide any medical expertise or advice, because everyone’s single ventricle journey is unique. While medical topics and experiences will inevitably arise in conversations around single ventricle disorders, we ask you to refrain from providing any medical advice to your matches.

Q: What happens if my matches aren’t a great fit for me and my questions?

A: As our matching pool continues to grow, so will your ability to match with new Linking Heart members! You will have the ability to refresh your matching page to meet new matches. Additionally, you will have the ability to customize the matching criteria used to generate your matches. For example, you can choose to connect with matches who have similar matching criteria to you (same age of patient, diagnosis, and geographic location) or opt to match with other members based solely on diagnosis, or geographic location, etc.

Q: What is the cost to join?

A: This program is free to join.

Q: How secure is the matching program?

A: The matching program is provided on a secure site with our partner program, CNXION. Matches and profiles are protected by the password secure site.

Q: Who do I contact with my questions?

A: Please contact Sisters by Heart at info@sistersbyheart.org.

Post Program Launch Updates to FAQs:

Q. Who can join Linking Hearts?

A. Linking Hearts is currently open to all parents and caregivers of single ventricle patients in the United States, including angel moms, dads, and caregivers. Linking Hearts is also currently available to patients ages 18 and older.

Q: How do I sign up to be a part of Linking Hearts?

A: In order to join the matching pool, you will need to register and create an account. To do this, you will need to create a username and password and tell us if you are a parent/caregiver, an angel parent/caregiver, or an adult patient. Then you will enter some information about yourself and/or your single ventricle patient, including: the patient’s age, diagnosis, and geographic location. These 4 criteria will be used to generate your matches. You will also have a list of topics that you can select as areas of special interest such as education, post-surgical outcomes, or mental health and resilience. You will also have the ability to upload a photo and write a short bio about yourself, your family, and what you’re looking to gain from this program, which will only be viewable to other members once you’ve accepted their match.

Q. How will I be matched with others?

A. Once you’ve registered and selected your matching criteria, you will see the names, photos, and profile information of at least 3 matches. You will be able to review these profiles and choose who you would like to connect with and you’ll click a “Connect” button. The program will then reach out to those individuals to ask if they would like to be connected. If they say yes, the program will notify you. You can come back to the matching page again at any time to search for new matches. You can also update your matching criteria and special interest areas at any time to update your matches.

Coming Late April 2022!!

TARA’S STORY

Tara McFadden is a 29 year old woman who wants to address the need for mental health care for individuals with Congenital Heart Defects. Tara was born with Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome and has been speaking with families in the CHD community since the age of 8. Over the years, Tara has talked to many parents of younger children and shared her life experiences with them. Meeting so many other individuals with a CHD made her feel part of a community.

Tara’s heart condition has impacted her physically. When she was younger she always wanted to play sports. However, she lacked the endurance required to play at the competitive level. Accepting that fact was challenging. After many attempts at various sports and much frustration, Tara finally made peace with it and found other interests such as playing pool, baking and non-competitive swimming.

In fifth grade, Tara discovered that she had a learning disability and soon understood the importance of self-advocacy. She expressed the modifications she needed to succeed and even made sure to get the proper accommodations throughout college and grad school. While in college Tara worked in the Office of Specialized Services helping others with disabilities. She would speak about the importance of being a self advocate and how to use your accommodations to help achieve academic success.

In fifth grade, Tara discovered that she had a learning disability and soon understood the importance of self-advocacy

Self advocacy has helped Tara not just academically, but also medically. She started experiencing some irregularities with her heart when she was in college. She was working with a team in NYC and did not agree with their care plan so she searched for a different team of doctors. After transferring hospitals, she felt confident in the new team. Tara emphasizes the importance of listening to your body, learning all you can about your CHD, and addressing issues when they arise.

Tara studied social work in college. Her social work classes allowed her to better understand human behavior and herself. She realized how all that she has gone through makes her see the world through a different lens than her classmates. Tara graduated with a masters in social work in 2017 and earned her LSW (license in social work) shortly thereafter. Today, Tara works with adults with developmental disabilities in a day habilitation program teaching them daily living skills and emotional regulation.

After graduating with her LSW Tara ran a CHD support group, for a brief period of time, where she discovered that individuals with a CHD have like mindsets. While running the group she found that they all share similar experiences and speak the same ‘language’ of medical terminology.

Tara is currently working on a new project, CHD Mindset, which is mental health therapy for people with Congenital Heart Defects. Look to follow her in the New Year @chdmindset on facebook and instagram.

The Heart-Brain-Body Connection: A Guide for Effective Parent-Led School Advocacy

Dr. Cheryl L. Brosig, PhD

Professor of Pediatrics and the Chief of Pediatric Psychology and Developmental Medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Kyle Landry

Educational Achievement Partnership Program Manager at Children’s Wisconsin

When I last posted several weeks ago I alluded to the 5 essential steps the Herma Heart Institute’s Educational Achievement Partnership Program uses to advocate for cardiac patients within the school setting. As a parent it’s likely you speak with your child’s school team on a daily basis. While check-ins and other informal conversations are generally positive and productive, I often hear parents say they just can’t get the message across of how their child’s learning challenges may be related to their medical condition(s). This is where the logic chain comes into play!

The Heart-Brain-Body Connection

When educating school staff on how pediatric heart disease (as well as other physical and mental health conditions) affect your child’s learning and development, it is important to create a logic chain which links the child’s medical condition(s), to how it affects their physical health, to how it physically impacts brain development, to how it impacts all aspects of neurodevelopment, and finally to how it results in educational challenges observed within the classroom setting. Don’t let that overwhelm you…I’m here to walk you through step-by-step.

Here is when I bust out the logic chain:

When requesting an IEP/504 Plan evaluation for the first time (initial evaluation)

When requesting revisions be made to a current IEP/504 Plan (review/revise request)

During annual health planning or update meetings with school staff (whether they have an IEP/504 Plan or not)

When educating new teaching or support staff about the child’s medical history (whether they have an IEP/504 Plan or not)

I always make sure I write my logic chain up as a formal letter and save it to a PDF so it cannot be edited. I then email a copy of my letter to all staff working directly with the child on one email thread, and then hand deliver the second copy to a special education teacher, school psychologist, school social worker, or other key staff member my child works with (regular education teacher is appropriate for a child who has never had an IEP/504 Plan before) “for their records.” For some reason receiving it twice shows you mean business, but in a totally approachable way.

When prepared in advance of an IEP/504 Plan meeting (regardless of an initial or revision meeting) I specifically ask for 10 minutes at the beginning of the meeting to share the letter with the team and answer any questions about how the child’s medical condition directly relates to challenges they may be seeing in the classroom. This step is very important because it sets the foundation for what the rest of the team should be considering when determining qualification or modifications. It’s easy to skim the letter or fail to read it all together, but when a parent comes to a meeting with prepared talking points, everyone listens.

Ok, let’s tackle drafting this letter together!

To start your letter always begin with some sort of brief intro paragraph. I recommend stating your child’s name, acknowledging their complex medical history, identifying concerns in the schools setting, and requesting formal support ensuring that they have access to all of the support services necessary to equitably participate (and thrive!) in an academic setting. Here’s an example you could customize:

I am writing today on behalf of my child/son/daughter, [name]. [Name] was born with a complex congenital heart defect requiring multiple corrective surgeries during his/her first few weeks of life. While [name] is [stable/doing well/etc.] from a cardiac perspective, he/she is at risk for associated neurodevelopmental deficits and differences. Considering [name’s] recent/on-going classroom challenges in [reading/writing/math/executive functioning/attention/behavior/social-emotional/etc.] I would like to request [a formal IEP/504 Plan evaluation/re-evaluation/review and revise meeting/etc.] to ensure he/she has access to all of the support services necessary to equitably thrive in an academic setting.

Let’s dive in…

Step 1: Clearly Name and Describe the Medical Conditions(s)

Clearly state your child’s diagnosis/ses and describe what that means in brief layman’s terms. If they have several different diagnoses it’s ok to list them all in bulleted form.

Here are some examples:

Artial Septal Defect: a hole in the muscle wall (septum) that typically separates the upper right and left chambers of the heart (atria). As a result, some oxygenated blood from the left atrium flows through the hole in the septum into the right atrium, where it mixes with oxygen-poor blood and increases the total amount of blood that flows toward the lungs.

Coarctation of the Aorta: a narrowing or constricting of the aorta, the large vessel that carries the oxygen-rich blood from the heart to the brain and body. When this artery is constricted, the heart has to work much harder to force blood though the narrowing and on to the brain and body, overworking the heart over time.

Truncus Arteriosus: a rare defect of the heart in which a single common blood vessel comes out of the heart, instead of the usual two vessels (the main pulmonary artery and aorta), which causes mixed, oxygen-poor blood to be circulated throughout the brain and body.

Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome (HLHS): a severe congenital heart defect in which the left ventricle is critically underdeveloped at birth, significantly impairing the heart’s ability to pump blood to the brain and body.

One or two sentence is plenty - how their cardiac anatomy is physically different and how that impacts or changes blood and oxygen circulation. Google is your friend, here. I search diagnoses all the time to write my layman’s definitions. Just beware, with lots of different cardiac diagnoses and lots of different combinations of defects, you need to be sure that what you are describing actually matches your child’s unique anatomy.

Step 2: Describe the Body and Health Impact

For this section we simply need to make a statement about how the CHD (or other heart diseases or irregularities), as well as any other relevant medical conditions, can impact the body from a physical perspective. I generally have one “bread and butter” sentence that I use and customize as needed to make this point clear.

Here it is…

Congenital Heart Defects (CHD) and other pediatric heart diseases may affect blood-oxygen circulation in the body, and may cause unique baseline symptoms that may require rest and recovery such as irregular heart rate, breathing disturbances, cyanosis (blue/gray coloring of the mouth, lips, and nail beds), low energy, fatigue, and may cause strength, vitality, and alertness limitations.

If your child experiences additional symptoms as a result of their diagnoses (i.e. headaches, dizziness, stomachaches, body temperature fluctuations, etc.) add those here as well.

Step 3: Describe the Brain and Developmental Impact

Great! Next, how is the brain potentially impacted? Once again, I will share the statement that works well for the EAPP. And once again, you can choose to use it or customize it in a way that makes most sense for your child.

Pediatric heart diseases, their treatments, and related complications are known to affect normal blood and oxygen flow, potentially delaying pre- and post- natal brain development.

Step 4: List Neuropsychological Deficits

Now we take that last sentence one step further…

In fact, significant research studies have suggested that children with heart disease often score lower in hand-eye coordination, fine and gross motor skills, social-emotional functioning, and language development than their typically developing peers. Behavior, attention, immaturity, and learning challenges are also much more common among children with heart disease.

Step 5: Describe Known Educational Challenges and List Challenges Observed

When it comes to the school setting, extensive research has shown lots of common educational challenges. Here are a few common things to consider:

Educational concerns can arise at different stages of development from preschool though adulthood.

New concerns may emerge when age level expectations increase in areas of independence, organization, attention, and academic skills.

Subtle neurodevelopmental deficits affecting multiple domains are extremely common and often result in more substantial academic concerns over time.

Neuropsychological deficits do not self-correct and these children simply cannot be expected to “catch-up” on their own.

Feel free to do your own additional research too!

Here is where you braid in your specific concerns for your child. Or better yet, further bulk up this section with the results from any formal neurodevelopmental testing that has been completed.

This section might look something like this:

At this time I have concerns related to [name’s]… (list away, but be specific! Share any examples that have been clearly observed in a classroom setting).

Academic challenges like those [name] is experiencing are very common with pediatric heart patients. These concerns often arise at different times from preschool though adulthood as independence, organization, and skill level demands increase. Subtle neurodevelopmental deficits affecting multiple domains may result in more substantial academic concerns over time as they do not self-correct and these children cannot be expected to simply “catch-up” on their own.

[Name] received a formal neuropsychological evaluation on [date] at [age]. This assessment included interviews, observations, and completion of both formal and informal tasks, as well as pencil and paper based testing. The completed evaluation report revealed the following diagnoses and impairments… (then list as applicable just as you did with the medical conditions – diagnosis and layman’s description).

Finally, wrap up your letter by restating the purpose. Don’t forget to sign off with your signature and contact info! If I was writing the letter, my closing paragraph might look like this:

Based on a combination of the known neurodevelopmental challenges related to pediatric heart disease and the challenges observed at home, in the classroom, and in the community, this letter should serve as a formal request for [a/an IEP/504 Plan evaluation/re-evaluation/review and revise meeting/etc.] to evaluate for [new/additional] educational services and/or accommodations. Please contact me at your earliest convenience to complete any necessary paperwork and schedule follow-up.

Ok, so your letter is done but your work isn’t!

Remember to send off your letter with a request for 10 minutes at the beginning of any related follow-up meeting to share this information with the team. Review your key talking points ahead of time and practice delivering a clear and concise message: these are my child’s medical conditions, this is how their brain and body are impacted (or at least at risk), and here are my concerns that I would like discussed as a team today.

Almost done, one last step. I urge you to talk about the importance of school support as a component of follow-up care and advocate for school liaison support within your own hospitals and cardiac centers. If you don’t have the right words to start the conversation, I do. Seriously, share my contact information. While my work is housed within Children’s Wisconsin, my mission is global. Your child matters to me and I am willing to put in the time, effort, and “dirty work” to advocate for the resources and support they deserve. I am also here to celebrate your successes – if these 5 steps transformed the way you were able to advocate for your child or their access to a quality education, I want to hear about it!

Stay tuned for the very anticipated launch of our new Educational Achievement Partnership Program webpage, loaded with inspiring patient stories and our most tried and true advocacy resources, this Fall!

ATTENTION DEFICIT HYPERACTIVITY DISORDER IN CHILDREN AND YOUTH WITH CONGENITAL HEART DISEASE-PART II

PART II: What to Do If You Think your Child with CHD May Also Have ADHD

David D. Schwartz PhD ABPP

Neuropsychologist, Texas Children’s Hospital

Associate Professor of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine

Katherine Cutitta PhD

Psychologist, Texas Children’s Hospital

Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine

Background

Children with congenital heart disease (CHD) are more likely to develop Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) than their peers. One recent study at Texas Children’s Hospital found that children with CHD (regardless of severity) were more than twice as likely to develop ADHD compared to all other patients. Other studies have shown that roughly 30% of children with more complex CHD have significant attention problems and/or hyperactive/impulsive behavior. In Part I of this Practitioner’s Post, we described the core symptoms of ADHD and placed them in the context of a broader model of self-regulation and self-control, and reviewed the etiology (causes) of ADHD with a focus on children with CHD. In Part II, we explain what to do if you think your child with CHD also has ADHD, with a focus on evidence-based assessment and effective treatment and management strategies.

PART II: What to Do If You Think your Child with CHD May Also Have ADHD

Assessment & Diagnosis

As discussed in Part I of this post, signs and symptoms that your child may have ADHD include attention problems, hyperactive behavior, and/or impulsivity that interferes with their development or daily functioning or causes significant distress. Many people express concern that ADHD is over-diagnosed. Research suggests that, in fact, it is both over-diagnosed and under-diagnosed. Boys with behavior problems and Black children are more likely to be misdiagnosed with ADHD, whereas girls, and children with “quieter” forms of ADHD (such as the inattentive subtype), often go undiagnosed. This is why accurate assessment by a qualified professional is so important.

If your child has a relatively mild form of CHD and has shown otherwise typical development (aside from possible ADHD symptoms), you might first discuss your concerns with your pediatrician. To assess for ADHD, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that the healthcare provider take a comprehensive history and gather information about the child’s behavior in different settings, and the best way to do this is through use of standardized behavior rating scales filled out by the child’s parents, teachers, or other caregivers (teens and adults may also complete a self-report form).

However, if your child has more complex CHD or shows significant developmental delays, a more comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation would be recommended. Specifically, comprehensive evaluation would be recommended for all children and youth with CHD who:

Required heart surgery in the first few years of life

Have cyanotic heart disease

Have a history of mechanical support

Have a history of heart failure and/or heart transplantation

Have other complications or comorbidities (like prematurity, stroke, or seizures)

Have significant developmental delays or learning problems

Have a genetic syndrome

Neuropsychological evaluations provide a broad assessment of cognitive and psychological functioning. Your child will be given tests that examine their intellectual functioning, attention, executive functioning, learning, memory, language, and sensorimotor skills, among other areas. The tests typically involve answering questions, solving puzzles, and the like—they do not involve brain imaging, blood work, or other medical tests.

The reason to seek out a more comprehensive evaluation is that children with complex CHD often have other neurodevelopmental and neurocognitive deficits in addition to ADHD symptoms, and the evaluation can place these difficulties in the context of your child’s medical history. After the evaluation is completed, you will receive a comprehensive report documenting your child’s cognitive strengths and difficulties, as well as extensive recommendations for school, home, and therapeutic intervention if indicated.

To arrange for a neuropsychological evaluation, you can ask your child’s cardiologist for a referral, look into whether your local children’s hospital has providers on staff, or look for a neuropsychologist (or an appropriately-trained pediatric health psychologist if no neuropsychologists are available) in your area.

Intervention & Treatment

Because of their executive deficits, children and youth with ADHD often need additional support from parents, teachers, and other adults to stay organized, remember what they need to do, and complete daily tasks within time expectations. Adult oversight and support is therefore often needed to ensure tasks get done, even for older adolescents. This can go against many parents’ belief that their teen is old enough to take care of these things on their own, but it is important to recognize that performance of these tasks is much more challenging for people with ADHD. Even adults with ADHD may need organizational help from significant others, for example to ensure that they make appointments or that the bills get paid on time.

That said, there are treatments and interventions that can help minimize the impact of these problems on a person’s daily life. Extensive research has shown that there are three treatment approaches that have been shown to be effective for children and youth with ADHD:

Behavioral therapy (including parent management training)

Environmental supports and accommodations

Medication, especially in combination with behavioral supports

Each of these approaches is discussed in detail below.

Behavioral therapy/behavior management training. Children with ADHD often need a modified parenting approach compared to their peers. They tend to do better with clear rules, predictable consequences, and consistency in parenting across caregivers. They may need help keeping track of time and navigating transitions, and rewards may need to be made more immediate and tangible to better guide their behavior. Behavior management training for parents (and classroom behavior management training for teachers) is a very effective approach that can help families get a better grasp on their child’s behavior and reduce the impact of ADHD symptoms on daily life. Organizational skills training can also be helpful for teens.

For more information on behavioral therapy for ADHD, see here and here.

Environmental supports. ADHD-related school problems are best addressed through development of a comprehensive school plan that targets the behaviors of greatest concern in the classroom. This is typically done through a formal, written plan designed in collaboration with the school. In the U.S., two federal laws govern how children with disabilities like ADHD and CHD receive supports and accommodations in the (public) school environment: Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

Section 504 is essentially anti-discrimination law designed to decrease barriers to educational opportunity. It applies to anyone with a disability that can affect their access to a free and appropriate public education. If a child qualifies, they will be given a written 504 Plan (parents should receive a copy) that provides classroom accommodations to ensure equal access to educational opportunity. Common accommodations for children with ADHD include preferential seating close to the teacher, extended time for tests and assignments, and organizational assistance.

The IDEA governs how states and public agencies provide early intervention, special education, and related services. To qualify for services under IDEA, the child’s disability must affect their educational performance and/or ability to learn and benefit from the general education curriculum. If the child qualifies, the school (in consultation with the family) will develop a written Individualized Education Program (IEP) that specifies learning goals and what the school will do to help student attain them. An IEP may also contain accommodations (such as a behavior intervention plan) similar to those found in a 504 Plan.

Private and parochial schools that do not receive federal funding are not bound by these laws, though many are still happy to work with families to develop an appropriate plan.

504 Plans and IEPs can both be implemented in the general classroom, and do not require the child to be placed in a special setting. By law, the school must place the child in the least restrictive environment possible to ensure adequate education. Of course, some students with more significant developmental or learning disabilities might benefit from part-time or even full-time placement in a resource classroom where they can get more individualized support.

For more information about school plans for children with ADHD, click here.

Medication. Medication can be life-changing for people with ADHD, reducing the core symptoms and giving them more control over their lives. ADHD medications should not change a person’s personality or make them seem like a “zombie”; if they do, this should be discussed right away with the prescribing physician, who can make changes to the medication or its dose.

A word about ADHD medication for children with congenital heart disease: Stimulant medications (amphetamine products and methylphenidate) are generally the most effective for treatment of ADHD symptoms, but there has been concern about potential adverse cardiac effects. A recent review article found “no evidence for serious adverse cardiovascular complications in children with known cardiovascular diseases including patients of congenital heart disease who are treated with stimulant medications,” but caution is still required when prescribing these medications for children with CHD. For example, studies suggest that stimulant medications may result in increases in blood pressure and heart rate. Consultation with a cardiologist before starting any ADHD medication is therefore strongly recommended.

For more information about medication for ADHD, click here.

Alternative treatments. Many parents are also interested in alternative approaches to treating ADHD symptoms. In general, there is currently no good scientific evidence that the following approaches work to treat ADHD or executive dysfunction: herbal supplements, homeopathic preparations, neurofeedback, or brain-training programs.

There is some limited evidence that micronutrient supplements such as omega-3 fatty acids might be effective in reducing ADHD symptoms, though more research is needed. Again, consultation with your child’s cardiologist is strongly recommended before starting any supplements to ensure there are no medical contraindications.

Finally, there is evidence that healthy living approaches may help alleviate some ADHD symptoms including executive dysfunction, though their effects are likely small. These generally beneficial approaches include:

Regular physical activity (keeping in mind any activity limitations your child may have)

A well-balanced diet of whole, minimally-processed, and nutrient dense foods that is low in added sugars, saturated fats, and sodium

Adequate sleep (10-13 hours/night for preschoolers, 9-12 hours/night for grade-school age children, 8-10 hours/night for teens)

Practices such as mindfulness and meditation

Summary & Conclusions

Children with CHD have an increased likelihood of having ADHD and executive dysfunction, especially if they have more complex, cyanotic, or palliated disease. Careful evaluation is important to best understand the symptom presentation and the degree to which symptoms might be part of a broader neurodevelopmental disorder. Surveillance of symptoms over time is also crucial, as the picture may change if they experience chronic hypoxemia or heart failure, or undergo cardiac surgery or heart transplant. ADHD interventions are similar for children with and without CHD, and include behavioral therapy and environmental modifications. Medication can also be quite helpful for symptom reduction, but must only be used under the supervision of a cardiologist. When all is said and done, people with ADHD and CHD can be quite successful in their lives, especially when given the appropriate supports.

Selected References

Berger S. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder medications in children with heart disease. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2016 Oct;28(5):607-12. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000388. PMID: 27261563.

Gonzalez VJ, Kimbro RT, Cutitta KE, Shabosky JC, Bilal MF, Penny DJ, Lopez KN. Mental Health Disorders in Children With Congenital Heart Disease. Pediatrics. 2021 Feb;147(2):e20201693. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1693. Epub 2021 Jan 4. PMID: 33397689; PMCID: PMC7849200.

Marino BS, Lipkin PH, Newburger JW, Peacock G, Gerdes M, Gaynor JW, Mussatto KA, Uzark K, Goldberg CS, Johnson WH Jr, Li J, Smith SE, Bellinger DC, Mahle WT; American Heart Association Congenital Heart Defects Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, and Stroke Council. Neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with congenital heart disease: evaluation and management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012 Aug 28;126(9):1143-72. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318265ee8a. Epub 2012 Jul 30. PMID: 22851541.

Shillingford AJ, Glanzman MM, Ittenbach RF, Clancy RR, Gaynor JW, Wernovsky G. Inattention, hyperactivity, and school performance in a population of school-age children with complex congenital heart disease. Pediatrics. 2008 Apr;121(4):e759-67. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1066. PMID: 18381503.

Dr. Katherine Cutitta

Katherine Cutitta, PhD, is an Assistant Professor at Baylor College of Medicine and serves as the dedicated clinical health psychologist for the Heart Center at Texas Children’s Hospital. She works with families and children with congenital heart disease, as well as adults with congenital heart disease to help improve quality of life and establish heart healthy habits with managing congenital heart disease.

Dr. David Schwartz

Dr. Schwartz is a pediatric neuropsychologist at Texas Children’s Hospital and Associate Professor of Pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine. He has long worked with children, youth, and young adults with congenital heart disease. Dr. Schwartz currently conducts neuropsychological evaluations of patients seen through the Texas Children’s Hospital Cardiac Developmental Outcomes Program and Heart Transplant Program, and he has completed research on cognitive outcomes in adult survivors of CHD.

ATTENTION DEFICIT HYPERACTIVITY DISORDER IN CHILDREN AND YOUTH WITH CONGENITAL HEART DISEASE- PART I

PART I: What is ADHD and What Does It Look Like in Children with and without CHD

David D. Schwartz PhD ABPP

Neuropsychologist, Texas Children’s Hospital

Associate Professor of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine

Katherine Cutitta PhD

Psychologist, Texas Children’s Hospital

Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine

Background

Children with congenital heart disease (CHD) are more likely to develop Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) than their peers. One recent study at Texas Children’s Hospital found that children with CHD (regardless of severity) were more than twice as likely to develop ADHD compared to all other patients. Other studies have shown that roughly 30% of children with more complex CHD have significant attention problems and/or hyperactive/impulsive behavior. In Part I of this Practitioner’s Post, we describe the core symptoms of ADHD and place them in the context of a broader model of self-regulation and self-control, and review the etiology (causes) of ADHD with a focus on children with CHD. In Part II, we explain what to do if you think your child with CHD also has ADHD, with a focus on evidence-based assessment and effective treatment and management strategies.

PART I: What is ADHD and What Does It Look Like in Children with and without CHD

ADHD is one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders, affecting roughly 1 in 10 school-age children and adolescents. It is characterized by difficulties with focus and paying attention, hyperactive or restless behavior, and a tendency to act without thinking (impulsivity). People with ADHD often have more difficulty waiting, may struggle to motivate themselves to complete boring or demanding tasks, and can find it challenging to manage their time and stay organized. At the same time, ADHD may be associated with positive characteristics including a high energy level, creativity, and an ability to hyper-focus on tasks perceived to be especially interesting. People with ADHD can be successful in their lives, but to do so they often need support and accommodation.

ADHD is defined based on symptoms—there is no blood test, and it cannot be diagnosed based on a brain scan or other physiological measure. Diagnosis is based on the clinical history (usually taken by a pediatrician or psychologist) and parent and teacher ratings on standard behavioral questionnaires. The clinician will also rule-out alternative explanations for the symptom presentation, and to screen for comorbid conditions such as learning disabilities, behavioral disorders, anxiety, and depressive disorders.

To meet criteria for an ADHD diagnosis, the child has to show symptoms of inattention and/or hyperactive/impulsive behavior for at least 6 months in at least two settings.

Children with inattention have problems focusing and paying attention, especially on tasks that they find boring or mentally demanding; they may also get distracted more easily, and have difficulty keeping their mind on one topic.

Children with hyperactivity may be overactive and have difficulty staying still; they may act impulsively, without thinking through consequences first; and they may have difficulty with waiting, and choose immediate rewards rather than wait for something potentially better.

There are three subtypes of ADHD. Children who only show attention problems but are not hyperactive are considered to have the Predominantly Inattentive Presentation of ADHD (which used to be called ADD). Children who are hyperactive without obvious attention problems are considered to have the Predominantly Hyperactive-Impulsive Presentation, and children who have both attention problems and hyperactivity are considered to have the Combined Presentation (this is the most common presentation). It is important to keep in mind that the symptoms by themselves do not warrant a diagnosis of ADHD unless they also cause impairment and have a significant impact on the person’s daily life.

An additional criterion for diagnosis is that symptoms have to have been present before age 12. However, a kind of secondary or acquired ADHD has been recognized as an outcome of brain injury that can occur at any age. For example, an older adolescent who has a stroke after heart transplant may develop attention problems that meet all of the other criteria for ADHD except for age of onset. While there is some disagreement among professionals about whether a diagnosis of ADHD can be given if symptoms first arose after age 12, many still find a diagnosis useful in these cases, as it can help guide treatment interventions.

For more information about ADHD, click here.

ADHD and Executive Functioning

ADHD is associated with deficits in executive functioning, which refers to a set of abilities involved in controlling and regulating your own behavior, either in response to what’s happening in your immediate environment, or in the service of longer-term goals. There are different models of executive functioning, but most include three core abilities:

Inhibition – stopping an initial response or reaction, which gives you time to think about alternatives. For example, a child may inhibit himself from grabbing a cookie and ask instead, or from blurting out an answer in class and instead raise her hand.

Working memory – the ability to hold information in mind, often while using it in some way. An example might be figuring out in your head how much change you should get back from a purchase, or weighing different responses to a problem in your mind.

Shifting (or “mental flexibility”) – the ability to shift attention from one thing to another, change tasks, or choose an alternative response. Examples include shifting attention from a video game to get washed up for dinner, or changing your approach when something you’re doing isn’t working.

People with ADHD typically show deficits in all three core executive functions. They have difficulty inhibiting behaviors, keeping information in mind without getting distracted, and shifting to a different idea, task, or response (or, alternatively, they may shift too frequently, and have difficulty staying on one topic). As a result, they may also have difficulty with more complex executive functions—such as planning, problem-solving, and decision-making—which rely on these three basic abilities.

Some researchers have argued that ADHD can be thought of as an executive function deficit disorder, a disorder in self-regulation and self-control. From this point of view, attention problems can be thought of as a deficit in controlling what you pay attention to.

Almost no one has difficulty paying attention to things that are interesting and “capture your attention”—the problem is when you have to make yourself focus on something boring or mentally demanding. A common example is playing video-games.

Parents will often say that their child can’t have ADHD because they can sit and play video-games for hours, but the real problem is that they can’t easily stop playing and shift to a different task—which is why they may have a huge tantrum if made to stop. Similarly, hyperactivity can be thought of as a difficulty with controlling excess movement, and impulsivity with controlling an impulse to say or do something without thinking about it first.

Difficulty with controlling emotional responses is less often talked about, but may be just as common in ADHD as deficits in attentional and behavioral control. Everyone experiences a surge in emotion when frustrated, excited, or upset, but then a counter-regulatory response usually kicks in to calm us enough to pause and consider how best to respond. Individuals with ADHD often have difficulty with putting the brakes on their emotional reactions. They tend to show poor frustration tolerance, and are more impatient, excitable, and quick to anger. They may also have more difficulty distracting themselves from whatever upset them, and shifting their attention to something else.

Finally, we sometimes also see motivational deficits in children and youth with ADHD. As noted, people with ADHD tend to be more strongly motivated by immediate rewards and have difficulty with deferred gratification, and they find it more difficult to “force themselves” to complete boring or mentally-demanding tasks. This is why using immediate rewards can be especially effective for children with ADHD. It is also why these children may have an especially hard time shifting attention away from video games, which actively engage the reward circuits in the brain. It is important to understand that such motivational deficits are likely brain-based and do not reflect “laziness,” defiance, or a lack of a desire to please others.

How can ADHD affect my child’s daily life?

ADHD can have pervasive effects on a person’s life. School problems are common. Children with ADHD may daydream in class, get distracted easily, and have difficulty staying focused on work (especially mentally-demanding work). Younger children may exhibit disruptive behavior in the classroom (or at home), resulting in a pattern where they are frequently reprimanded and in trouble, which can in turn result in a negative self-image as a “trouble-maker” or “bad kid.” They may also have more difficulty making and keeping friends due to inattention to social cues, immature or overly silly behavior, or difficulty keeping their hands to themselves.

Adolescents are expected to be responsible for staying on top of their schoolwork, managing their time, and meeting due dates, all of which may be more challenging due to the organizational and executive difficulties that come with ADHD. Teens with ADHD are also more prone to impulsive, risk-taking, and rule-breaking behavior. They are more likely to become parents at an earlier age, have more driving accidents, and may “self medicate” with alcohol or other drugs. Adults with ADHD may have more difficulties sticking with a job and maintaining long-term relationships.

Children with chronic illnesses like CHD often have to follow medical regimens such as taking medication at a certain time each day, which become their responsibility as they get older. Forgetfulness, disorganization, and inattention can all affect a youth’s ability to stay on top of a medical regimen, making parental oversight especially important.

So what causes ADHD, and how is it linked to CHD?

ADHD is considered a neurodevelopmental disorder, meaning most people are born with it, show symptoms in childhood, and may have delays in their development as a result. ADHD is highly heritable, which means it runs in families due to genes that get passed down from parent to child. If you have ADHD, your child is more likely to have it too.

Prenatal factors can also play a role in the development of ADHD. For example, fetal exposure to alcohol, nicotine, and other substances increases the risk that the child will have ADHD. In addition, children born prematurely also have a greater risk of ADHD. The basic idea is that, early in life, the developing brain is especially vulnerable to insult and injury, and one of the most common outcomes of early insult is ADHD.

It is this early vulnerability that places children with CHD at increased risk for ADHD. Congenital heart defects can result in reduced blood flow (ischemia) and reduced oxygen (hypoxemia) to the brain, which can have an effect on how the brain develops prenatally and in early childhood. Children with complex CHD often show immature brain development at birth, with reductions in both cerebral gray and white matter; and these differences are associated with increased risk for neurodevelopmental disability. In fact, children with CHD closely resemble children born prematurely in terms of their neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Cardiac surgeries, especially in the first few years of life, and associated procedures such as being placed on cardiopulmonary bypass or ECMO, can also affect how the brain develops, and add to the risk for ADHD symptoms. Children with cyanotic heart lesions, or with medical co-morbidities, are also at higher risk.

One of the brain regions most vulnerable to early insult are the frontal lobes, which take up about 1/3 of the total surface area of the brain. The largest part of the frontal lobe is the prefrontal cortex, which is the brain region most closely involved in executive functioning. It therefore isn’t surprising that executive dysfunction is among the most common (if not the most common) neurocognitive deficits seen in people with CHD.

Changes in symptoms over time

While most people with ADHD do not “grow out of” the disorder, the symptom presentation can change as children get older. Hyperactive behaviors are most common in younger children, and may moderate over time, especially as the child enters adolescence. Attention problems typically become more evident as children reach grade-school age and expectations for focus and concentration increase. While impulsivity often remains evident throughout development, it may become a different kind of problem in adolescence, as youth begin to have greater freedom from their parents, start to drive, and may be faced with risky choices such as whether to drink alcohol or use other substances, or to engage in unprotected sex. Teens may also begin to have more difficulty with self-esteem, anxiety, and depressed mood.

Children and youth with CHD may face a different kind of change in ADHD symptoms related to their heart disease. Chronic hypoxemia and heart failure may result in worsening attention over time. Complications of later-occurring heart surgeries, placement of ventricular assist devices, and transplant may also result in a worsening of symptoms. For children and youth with CHD, ADHD symptom surveillance is important, as is periodic re-evaluation every couple of years, or following any new significant cardiac event or surgery.

Dr. Katherine Cutitta

Katherine Cutitta, PhD, is an Assistant Professor at Baylor College of Medicine and serves as the dedicated clinical health psychologist for the Heart Center at Texas Children’s Hospital. She works with families and children with congenital heart disease, as well as adults with congenital heart disease to help improve quality of life and establish heart healthy habits with managing congenital heart disease.

Dr. David Schwartz

Dr. Schwartz is a pediatric neuropsychologist at Texas Children’s Hospital and Associate Professor of Pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine. He has long worked with children, youth, and young adults with congenital heart disease. Dr. Schwartz currently conducts neuropsychological evaluations of patients seen through the Texas Children’s Hospital Cardiac Developmental Outcomes Program and Heart Transplant Program, and he has completed research on cognitive outcomes in adult survivors of CHD.

Understanding the ADHD Diagnosis

Mark Beidelman, PsyD

Pediatric Neuropsychologist at Stanford Children’s Health

What is ADHD

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder or ADHD is a relatively new diagnosis, but the clusters of symptoms that make up this diagnosis have been identified and categorized under different names dating back to at least 1798 (Crichton 1798). What we now know of as ADHD first appeared in the second edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-II) in 1968. Through the various iterations of DSM-III (1980), DSM-IV (1994), and DSM-5 (2013) there have been subtle changes to the classification of these symptoms as a unified condition. As a professional or as a parent, it’s important to not get overly focused on the diagnostic criteria or the changes over time, but instead to think about what aspects of functioning are impaired in this diagnosis and what steps can be taken to make functional improvements.

Currently in DSM-5 ADHD is defined as “A persistent pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity that interferes with functioning or development, as characterized by Inattention and/or Hyperactivity and Impulsivity.”

Inattention:

Often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, at work, or during other activities

Often has difficulty sustaining attention in tasks or play activities

Often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly

Often does not follow through on instructions and fails to finish schoolwork, chores, or duties in the workplace

Often has difficulty organizing tasks and activities

Often avoids, dislikes, or is reluctant to engage in tasks that require sustained mental effort

Often loses things necessary for tasks or activities

Is often easily distracted by extraneous stimuli

Is often forgetful in daily activities

Hyperactivity and impulsivity:

Often fidgets with or taps hands or feet or squirms in seat

Often leaves seat in situations when remaining seated is expected

Often runs about or climbs in situations where it is inappropriate

Often unable to play or engage in leisure activities quietly

Is often “on the go,” acting as if “driven by a motor”

Often talks excessively

Often blurts out an answer before a question has been completed

Often has difficulty waiting his or her turn

Often interrupts or intrudes on others

Now, you might be thinking that you have a hard time sustaining attention on tasks, or everyone is reluctant to engage in tasks that require effort…or something like that. This might be true, but the individual symptoms of ADHD are best thought of as part of the grey scale of personal differences, or what makes us who we are. It is only when we see these symptoms clustered in a way that meets a certain severity and frequency threshold and see functional impairments in multiple settings that we consider ADHD.

One more thing about diagnosis before we move on.

There are three “types” of ADHD, which are:

Predominantly Inattentive Presentation

Predominantly Hyperactive/Impulsive Presentation

Combined Presentation

So, ADD is no more! Now ADD is called ADHD, predominantly inattentive presentation, and I suspect ADHD hyperactive/impulsive presentation and ADHD combined presentation explain themselves (i.e., more hyperactive symptoms for hyperactive/impulsive presentation, and a mixture of inattention and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms for combined presentation).

So, if I have explained the content in the above paragraph well enough, we can now understand you could have attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, while simultaneously being the least hyperactive person on the planet (so long as you are inattentive enough). Another consideration is that attention is not an all or nothing concept.

A comment I frequently hear from families is something along the lines of, “While we agree our child has difficulty attending to certain things (e.g., school, chores, books), they can attend or even hyper-focus on things they enjoy (e.g., sports, activities, video games), so how could this be ADHD?” To answer this, it is best to think about ADHD as not a pure deficit of attention, but instead as a difficulty regulating attention effectively. Meaning people with ADHD might have difficulty sustaining attention, ignoring impulses, shifting attention/transitioning appropriately, estimating time, organizing, etc.

ADHD, Executive Functions, and Emotions

Continuing this line of thinking from above, some would argue that ADHD is really a deficit of executive functioning. Executive functioning is a term used to describe an array of cognitive skills that include but are not limited to inhibitory control, working memory, cognitive flexibility, reasoning, problem-solving, planning, etc. My simplified definition of executive functioning is coordinating two mental or cognitive skills to solve one task/problem. Given the breadth of content around executive functions and how those executive functions might play out in daily life, let’s just focus on how attention could impact executive functioning and some of the additional consequences of ADHD.

ADHD and executive functioning are somewhat of a blurry line, in fact, some people even consider control of attention and impulse control as part of executive functioning. For our purpose on this much larger topic, let’s just say that difficulties with regulating attention and impulses will make it difficult to successfully coordinate multiple cognitive skills in an organized fashion.

ADHD and emotions are also complex. Emotion regulation difficulties are also common in individuals with ADHD, but not inherently part of the ADHD diagnosis. Symptoms of anxiety and depression have a higher than chance co-occurrence in people with ADHD.

The reasons for these emotional difficulties are likely multifactorial and could even be explained by different mechanisms in the same person. We will list a few relationships between ADHD and emotion regulation, anxiety, and depression. There can be impulsive behaviors that lead to interpersonal, academic, occupational, or relationships difficulties. Poor attention can make people feel lost or behind at school, work, or activities, which can increase anxiety. Difficulties with academic or work functioning can impact esteem/mood and lead to symptoms of depression. This is not an inclusive list, but it is important to realize that ADHD is not just about attention. A better way to think about ADHD might be to realize how these clusters of systems impact the whole person in academic, interpersonal, occupational, and introspective ways.

The good news is there are successful evidenced based therapies (behavioral therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, to name a few), behaviors/techniques (mindfulness practice, meditation, exercise, sufficient sleep), and medications (even with individuals with congenital heart disease) that can make lasting changes on attention, executive functioning, and emotional functioning.

There is a lot more to unpack about all this, including the connection between ADHD and Congenital Heart Defects. In the next few articles, this series aims to provide a deeper dive into this connection and what therapies and management strategies are available to parents today.

Dr. Mark Beidelman

Dr. Beidelman is a pediatric neuropsychologist at Stanford Children’s Health. He has studied neuropsychological functioning through the lifespan, but currently focuses on pediatric populations. He currently splits his time between various clinics that include: Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics, Single Ventricle Program, Cardiovascular Connective Tissue Disorders Program, Spina Bifida Clinic, Stroke Team, and the Center for Interdisciplinary Brain Sciences Research. He also has a pug.

Taylor’s Story

Taylor Hartzel Houlihan is a 24-year-old medical student, dancer, wife, daughter, and sister. She also happens to be a patient with Fontan circulation.

After her open-heart surgeries at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, she developed an interest in medicine and a passion for caring for others with congenital heart disease. Despite the challenges of growing up with CHD, Taylor refused to allow her condition to define her limits. She trained in classical ballet for 13 years, graduated as valedictorian from high school, and pursued the pre-medical track in college. Taylor is currently a third year medical student at Thomas Jefferson University and assists with Fontan research at CHOP. In addition to her studies, she maintains a rigorous exercise schedule reminiscent of her past ballet training. Recently, she started a social media account to share her medical journey, educate others about living as a Fontan, and offer hope to families with their own CHD stories.

If you are interested to find out more, you can follow her on Instagram or Facebook @FontanwithaFuture.

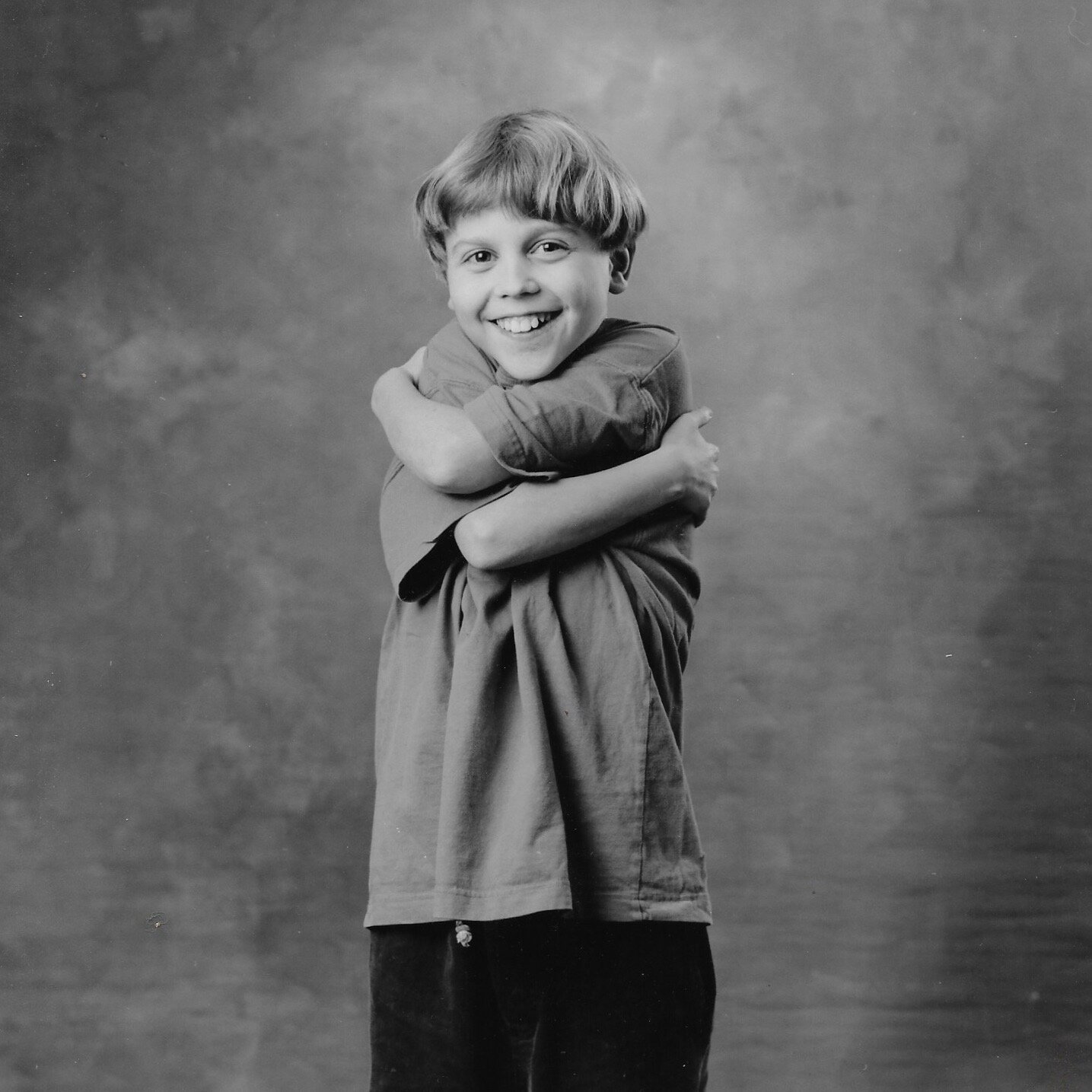

Donor Highlight: The Allen Family

When we first found out Carter was going to be born with HLHS we naturally went to the internet to find out as much information as possible on this terrifying diagnosis. That’s when we happened upon the Sisters By Heart website. There we found an abundance very helpful information and we’re able to request a care package for newly diagnosed families. This was particularly helpful as we knew nothing about the road ahead.

Carter had his Norwood and Glenn and things seemed to be going well. Shortly after his Glenn however he went into progressing heart failure and the decision was made to list him for heart transplant. He received his gift of life just before he turned 7 months old. The items in the care package and the information from both the website and Stacey were a vital part of our journey. Stacey even came and visited us in the hospital. It was incredibly helpful to talk with someone that had experienced some of what we were experiencing.

Once Carter was on the path to recovery we looked into how we could give back to the group which helped us navigate the most difficult of times.

Both of us work at Costco and our employees company wide do a United Way Foundation campaign. We looked into it and discovered we were able to select a charity of our choice for our donations to go to. We knew Sisters by heart was where we wanted to send those funds. This is a campaign Costco does every year and we continue to select SBH to receive our donations. For the past few years we have been apart of organizing a charity golf tournament with proceeds being split between SBH and another charity. Our continued support of Sisters By Heart is just our family doing a small part to help the wonderful group that guided us and supported us through our sons life threatening battle. We could never repay them but any small help we can provide will hopefully let them continue to help families of kiddos born with congenital heart defects.

Written by Carter’s dad, Matt Allen

School Advocacy: The Missing Link in Cardiac Follow-Up Care

Dr. Cheryl L. Brosig, PhD

Professor of Pediatrics and Chief of Pediatric Psychology and Developmental Medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Kyle Landry

Educational Achievement Partnership Program Manager, Children’s Wisconsin

The details are different but the story is always the same – they fixed his heart, why is school so hard?

Children born with congenital heart defects and other pediatric heart diseases are at risk for neurodevelopmental deficits, delays, and differences due to a variety of factors, including prenatal brain injury, fetal cerebrovascular physiology and oxygen delivery, decreased brain maturity, the effect of cardiac surgery on the brain, and the long term effects of lengthy hospitalizations on development. Through years of research, neuropsychologists have learned, and families have witnessed, that children with heart disease may experience limitations in physical and mental strength, vitality, alertness and often score lower in hand-eye coordination, fine and gross motor skills, social-emotional functioning, and language development than their typically developing peers. Behavior, attention, immaturity, and learning challenges are also much more common among children with heart disease.

Though many children with heart disease will experience typical neurodevelopment early on, it isn’t uncommon for new concerns to arise at different stages from preschool through adulthood as independence, organization, and skill level demands increase.

These neurodevelopmental challenges may affect multiple domains and can result in more substantial academic concerns over time as these deficits generally do not self-correct and these children cannot simply “catch-up” on their own.

While schools have established special education programs and supports, educational teams often lack the medical expertise to identify the unique, often subtle, neurodevelopmental needs of cardiac patients. On the other hand, medical providers often focus on aspects of the patient’s physical health, may lack experience in the complex educational system, and do not typically communicate extensively with schools. To further complicate things, unlike heart disease which is diagnosed and treated by medical specialists, neurodevelopmental deficits may be separately identified by medical and school practitioners, using different metrics and qualification criteria, resulting in different follow-up and missed opportunities for early intervention. In fact, a 2014 study led by the Herma Heart Institute’s own Dr. Cheryl Brosig revealed that medical providers recommended academic support for cardiac patients over 3 times more often than schools were actually providing these services.

Even with the ongoing support of two highly qualified, well-intended teams, both advocating for the student’s best interest, our children continue to fall through the cracks.

Children’s Wisconsin’s Educational Achievement Partnership Program (formerly known as the School Intervention Program) supports Herma Heart Institute patients by providing care coordination services that extend far beyond the walls of the hospital to maximize quality of life. The EAPP places experienced educators specially trained in complex medical conditions and the related impacts of surgeries, treatments, medication, and complications on cognition, physical health, and neurodevelopment at the center of a coordinated care team to ensure clear and consistent communication among families, medical staff, school staff, and community care partners. Through this collaborative partnership, the EAPP removes the burden of translating technical medical information from families and educates school staff on the child’s unique cardiac anatomy and the related heart-brain-body connection.

While I could talk about the EAPP all day, here’s what I want you to know: the “secret sauce” is that there are no secrets!

Through this Sisters by Heart blog series you will learn more about ADHD and Executive Functioning challenges related to CHD and how you can help support your child most effectively. As the series wraps up, I’ll be back to share 5 essential steps that the EAPP uses to educate school staff on the unique heart-brain-body connections and give YOU the tools that the EAPP has used to achieved a 97% success rate getting cardiac patients new or expanded health and education plans that allow our patients to thrive in the classroom setting. You won’t want to miss it!

Dr. Cheryl Brosig

is a Professor of Pediatrics and the Chief of Pediatric Psychology and Developmental Medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin. She serves as the Medical Director of the Cardiac Neurodevelopmental Follow Up Program and the Educational Achievement Partnership Program in the Herma Heart Institute at Children’s Wisconsin. Her clinical and research interests focus on neurodevelopmental and psychosocial outcomes in children and families affected by pediatric heart disease.

Kyle Landry

is the Educational Achievement Partnership Program Manager at Children’s Wisconsin. Since starting the program in 2015, she has served over 500 children with pediatric heart disease by conducting comprehensive school assessments in the clinical environment and helping school staff implement interventions within the school setting. Landry has a bachelor’s degree in Early Childhood Education (2010) and a master’s in Cultural Foundations of Community Engagement and Education (2018) from the University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee. Landry’s previous teaching experience specializing in youth placed at risk for school failure illuminates her belief that every child should have equal access to quality education.

Sisters By Heart Education Series

It took me completely by surprise and hit me like a ton of bricks the day my son was diagnosed with ADHD, Inattentive Type. I was so confused. My son had incredible focus and he wasn’t hyper at all. Turns out, I had no idea what ADHD was. Actually, I take that back. I knew a LOT of things about ADHD, and they were all wrong. So, I didn’t start my journey of educating myself about ADHD from the bottom. I was below the bottom. I had to climb out of my hole of complete misunderstanding and even ignorance. What struck me the hardest was learning how closely it all ties in with Executive Functioning and how closely that ties in with anxiety and depression. My son, at the tender age of 8, was beginning to experience those effects as well. The more I learned, the more everything started making a lot of sense. The more I learned, the more I wished I had been better informed and prepared.

A recent study revealed that children with complex single ventricle CHD have 7 times higher odds of diagnosis or treatment for anxiety and/or depression. And further, it has been estimated that 50-75% of children with complex CHD are affected by Neurodevelopmental Disabilities – that’s a big fancy catchall word for ADHD, among others. I learned we aren’t alone.

In fact, several of us at Sisters by Heart with school aged children, have found ourselves among these numbers. As a result, we are both humbled and excited to launch the first of many continual educational programs featuring practitioner article series and webinars on key challenge areas faced by Single Ventricle patients and their families. We are grateful to the providers that have partnered with us so far to make this a reality.

We hope that our first series; “CHD and ADHD: What You Need to Know,” helps you as much as it has helped us.

Heart Hugs,

Lacie Patterson

Mom to Dylan (HLHS, Age 9)

Director of Fontan Families

Spring 2021 Learning Session

The NPC-QIC Spring Virtual Learning Session was a dynamic day of collaboration among 330 participants from across the country, including providers, parents, and patients. The meeting highlights included presentations and discussions around health equity, an update on the soon-to-be-launched Fontan Outcomes Network, and how to provide quality emotional and mental health care and services for patients and families.

NPC-QIC currently has more than 70 cardiac centers working together to improve care and outcomes for infants with HLHS. Outcomes to date are impressive, achieving and sustaining a 46% reduction in mortality during the interstage period.

The Learning Session is a bi-annual opportunity for participating centers, including their patients and families, to come together to share best practices, discuss critical topics of importance, and learn from one another.

Health equity presentations focused on how to find and examine data to identify disparities followed by some really honest dialogue about how to identify and change the causes of those disparities. Sessions on emotional and mental health covered the “NAP” method: Normalize + Ask + Pause. The emotional health breakout session included a tremendous presentation by a fellow HLHS mom sharing her interstage experience, including their stay at the Ronald McDonald House during the entirety of her infant's interstage period. An update regarding the Fontan Outcomes Network (FON) was met with much enthusiasm by providers and families. FON is a new learning network, building a registry to collect data on Fontan patients throughout their lifespan in order to improve outcomes for patients and their families.For more information on NPC-QIC and how to get involved, visit www.npcqic.org or email info@npcqic.org.For more information on FON, please visit www.fontanoutcomesnetwork.org

Donor Highlight- Angel Memorial Gifts