David’s Story

The following was written by David’s father, Jim, and wife, Anahied:

David was born on a Friday at Moncrief Army Health Clinic in Columbia, SC. He was supposed to be released to go home on Sunday two days after birth. That morning while being checked by the on-duty pediatrician in preparation for discharge, it was noted that he “had a murmur” and while it was most likely nothing serious, it was decided that he would be transferred to Richland Memorial Hospital for further evaluation. He was transferred by ambulance and after completing his mother’s discharge paperwork, she and I drove over in our personal vehicle.

We were a little concerned, but not overly so. His mother was mainly just angry that she hadn’t been allowed to take her baby home on Sunday as had previously been indicated.

As an aside, my mother - who was at the apartment taking care of David’s older brother - was a RN and was working at a fairly large hospital in Florida. She loved her job and would often talk about it. One of the things she had talked about was the idea of “clinical detachment”.

When we arrived, we were directed to the NICU. We were buzzed in. The first thing I saw was a nurse standing over one of those radiant warmer “beds”, and she - the nurse - was bawling her eyes out. I immediately thought “That is very BAD!”. Then another nurse met us and led us to that warmer. It was David laying there.

A pediatric cardiologist came and told us that he wasn’t sure, but that he thought David had a heart defect called Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome. He explained that if that diagnosis was correct, then David was in serious trouble. They had already called for a helicopter to transport David to the hospital at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston because they would be better able to determine if that was the condition David had, and - if possible - treat it.

The nurse who had been crying had gone somewhere and gotten a Polaroid camera and asked us if we wanted a picture with our son. The implication was that we may not get another chance. And she was still crying.

His mother and I stayed at the apartment that night. We did not sleep.

The next day the nightmare was confirmed. The available options were explained to us.

Heart transplant: At the time - 1988 - the only place in America where infant heart transplants were being done was at Loma Linda in California. The waiting list for hearts was very long, a high percentage of HLHS patients did not survive long enough to receive a heart, and the post-transplant longevity wasn’t very good.

Palliative care: David would be placed in as private an area of the NICU as they could find and be made as “comfortable” as possible (sedation) and we would be able to spend as much time as would or could until he passed. That was expected to be days.

Norwood procedure: These days a lot of people know about the Norwood procedure and some number of hospitals perform it. In 1988 there was Dr. Norwood (who I hope is now in Heaven playing with all the children he tried to save over the years) and Dr. Robert Sade.Dr. Norwood was at CHOP, and Dr. Sade was (is) at MUSC. This was really 2 possible options. We could have David transported to CHOP to have Dr. Norwood perform the Norwood procedure (there was about a 7 day wait for an available OR there), or we could have Dr. Sade perform the Norwood procedure there at MUSC (an OR had been booked for 2 days later just in case). Dr. Sade had worked with Dr. Norwood when they were both at Boston Children’s Hospital and were still in very close contact/collaboration. Dr. Sade did explain that he had not done many of these procedures, and they had not gone well, but that he had just spent considerable time at CHOP working with Dr. Norwood on revising his methods and felt that he would be better able to successfully perform the Norwood.

Since time was a bit of an issue, we decided to have Dr. Sade perform the Norwood. David was 5 days old. The surgery was a success, as were the 2 follow up surgeries that Dr. Sade performed (hemi-Fontan and Fontan). There were a lot of sleepless nights during those 18 months and a WHOLE bunch of hair lost. It was incredibly stressful and incredibly scary.

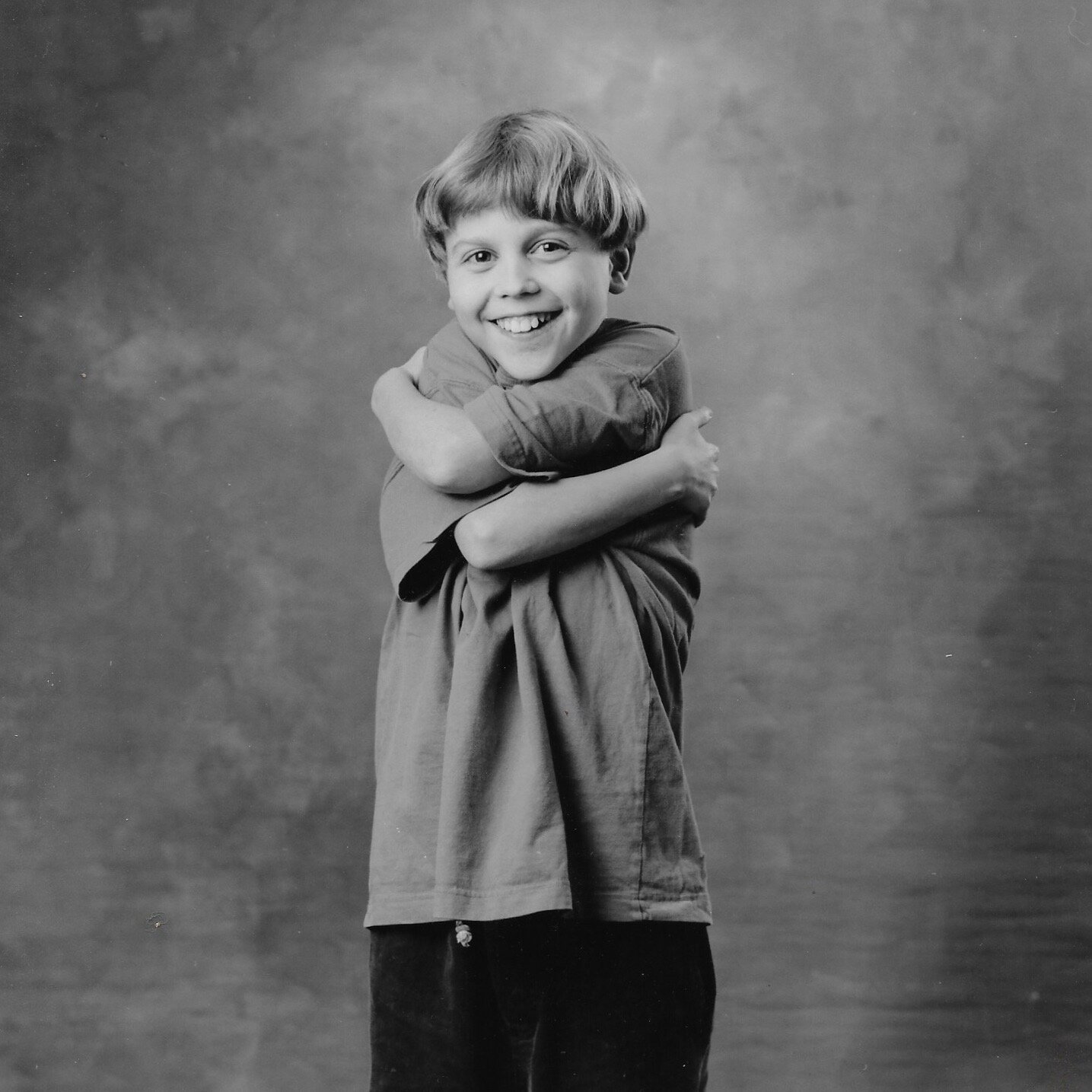

But David and his family were lucky. The prognosis for HLHS patients in 1988 was not very good. But we had a son who was alive, alert, intelligent, enthusiastic about life, and maybe just a little bit stubborn at times.

Most of the time he just appeared to be a regular kid who was a little small for his age. But he was a bit prone to “pneumonia” and asthma -and made fairly frequent trips to the pediatrician and local hospitals. It became a little amusing to watch the faces of nurses the first time they connected a pulse oximeter to him and saw his SpO2 was only in the 80s.

If he wasn’t “sick”, we tried to let him have as normal a life as possible. Completely normal isn’t possible. There are too many pills, too many times a day. Lasix wreaks havoc on a kid’s play schedule. But, you can get close.

Remember the little bit stubborn part? There was a fundraiser taking place. I believe it was a March of Dimes event. People would be walking laps on a track at a local park in exchange for donations. Kids could ride their bikes instead of walking. David had one of those hard plastic Big Wheel like tricycles. Hard plastic does not have good traction on asphalt. He insisted on riding his tricycle around and around that track. There were a couple of dips in the track. Between the lack of traction and his light weight, his front tire would start spinning each time he needed to go uphill. I made the mistake of just pushing him up. He got so mad! He wanted (needed?) to do it himself. So the rest of the laps I had to walk behind him and just give enough of a nudge with my toe that he could make it up, but he was doing the peddling. And he did all of the laps he had committed to for the fundraiser.

As he got older, his episodes of “pneumonia” became worse and more frequent. They were actually the beginnings of Protein Losing Enteropathy (PLE) and what was later (MUCH later) determined to be plastic bronchitis. Beginning just prior to adolescence, he had multiple hospital stays of up to 6 weeks. Again, scary times. There was always some discussion of heart transplant, but then he would improve and everyone would think that the PLE was behind us. Basically, his blood protein levels would drop down to the point to where his lungs would be wetter than normal and he would begin getting edema, ascites, pleural effusions.

Most hospitals - even in the Chicago area - either had little experience with post-Fontan HLHS patients, or weren’t aware of truly effective treatments (if they even existed). This was still pretty early in the “awareness” of HLHS and all that is involved in a post-Fontan HLHS patient’s care. There was a LOT of experimentation going on. Most of it was tried on David at one point or another. He was especially fond of the subcutaneous injections of Heparin…

But again, in between hospitalizations, he managed to have a fairly normal life. Boy Scouts for a while, attended a local military academy during high school (with a 6-week hospital stay his Junior year), had parties with friends, got into grilling and smoking meat. Got accepted to a local, well-respected university - but had to postpone entrance due to another illness episode.

Pretty much normal guy stuff with periodic reminders that his cardiac physiology is not like everyone else's. But the “reminders” were coming more and more frequently.

Eventually, one of the (MANY!) doctors treating David had heard that “some patients” had some success in stabilizing blood albumin levels and minimizing emergency admissions by receiving albumin infusions on a timetable that would keep his blood protein levels at above critical levels. This was not a cure, but it was a huge improvement in the stability of his health. Despite the fact that he was exhibiting PLE symptoms constantly for YEARS, he was able to attend some college (until he decided he didn’t need any more) and obtain and keep a full-time job. Not bad for a guy who’s chances for survival until adulthood weren’t considered to be very good back in 1988.

It has not been an easy road for his mother and I. There have been a lot of very scary hospital visits. But this is our son. We felt we had to do everything within our power to give him the best possible chance at the best possible life. And even with all the dark “episodes” that have been in his life, there have also been a lot of happy ones. And maybe the dark periods let us - or at least me - appreciate the happy ones even more. So at this point he’s in his twenties, working full time, partying with friends - probably has more friends than I do - has his driver’s license, and is being a man. We know that at some point “something” must be done to address the PLE in a more permanent manner, but we don’t know what that is yet or when it will occur. We’re kind of waiting to see what new medical developments occur. He’s not in a GREAT position, but it’s not a bad position and allows him a fairly normal life on the days he’s not getting an infusion of albumin.

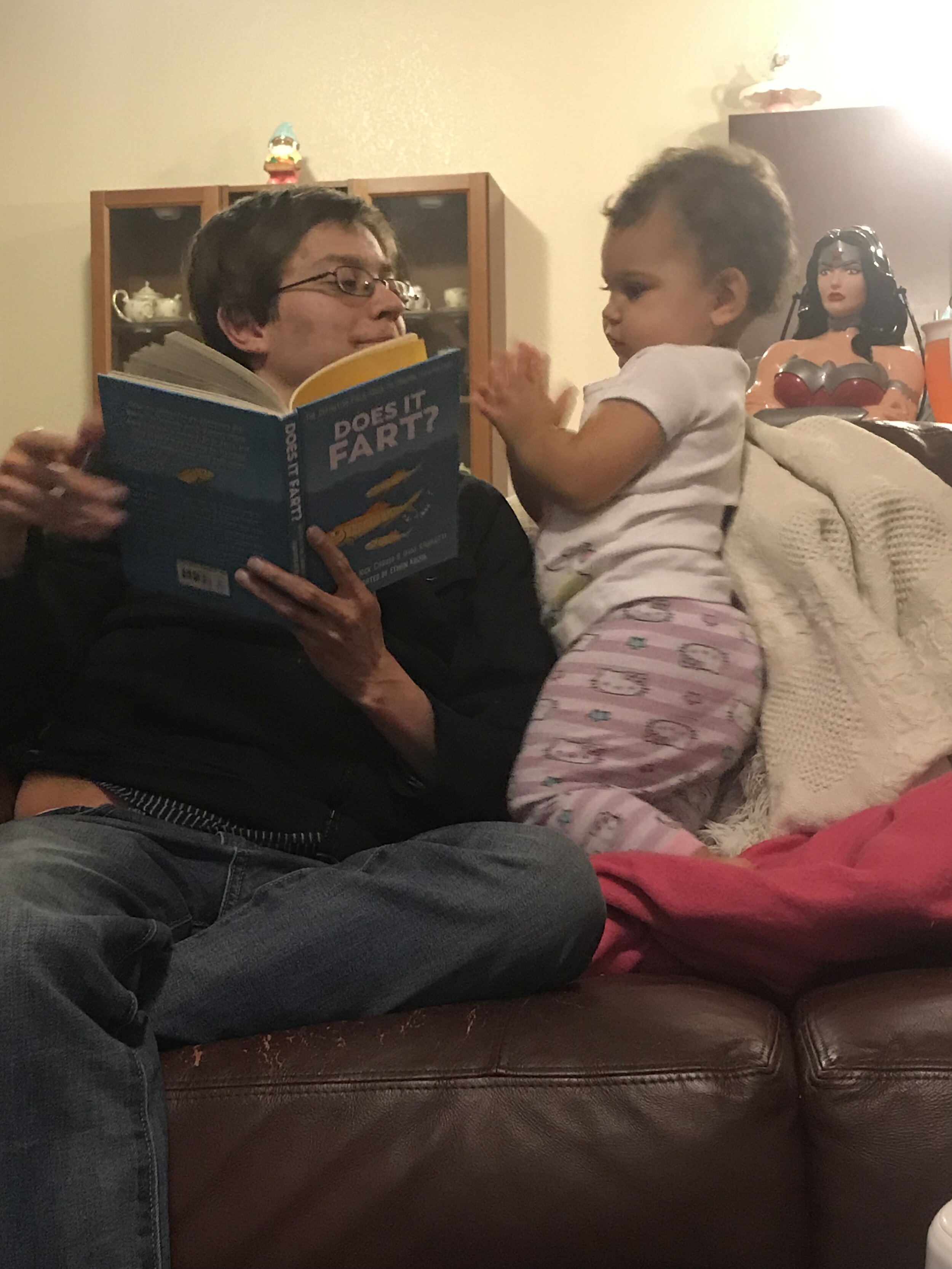

Life moves on, even among the stresses and uncertainties with the chronically ill. David graduated high school in 2009 and was even able to attend college. There, he met his wife and they were married in 2016. David currently works full time as a software developer, and his wife in electrical design. He and his wife welcomed their first baby, a perfectly heathy girl in 2018. You wouldn’t guess the extent of his illness, the way he chases his toddler around!

His health has not always been stable, particularly due to the PLE and plastic bronchitis issues- he had been hospitalized quite a bit in the last couple years. David, his wife, and a few wonderful friends traveled to Philadelphia, PA in July of 2020, for the lymphatic intervention procedure. The recovery was long, but we are so thankful for the work that had been done. This is currently the only hospital in the nation dealing with multi-lymph compartment failure in this way. Their procedure was able to increase the strength of his good ventricle, absolve him of the plastic bronchitis, and repair the PLE well enough that he no longer needs twice a week infusions. It feels a lot like a continuing line of miracles, predicated on the fortitude and knowledge of a select few heroes willing to work with this population. Every doctor, nurse and health care professional helped us get to this point- and for that, we are eternally grateful.

The time has come now for David to enter into a heart, and liver transplant program. Ultimately, we understood the progression of this disease would lead to this point. His co-morbidities stemming from his Fontan have become too great a burden on his body. While we truly wish he didn’t need to have a transplant, the fact that the option exists at all is incredible. You see, David is indomitable. His resolve to carry on with normalcy, even in an ICU or emergency setting has consistently kept us grounded. The fact that he has unfailingly worked full time, acts as a full time husband and father is wonderful- and honestly, probably good for his health! David has made it this far, in spite of every obstacle in front of him- and we think he’s seen more than his fair share. But, we are hoping, and expecting, for him to pass through this next stage with the same tenacious commitment towards life that we’ve always seen. He will be 33 in December of 2020. We will always have more than enough to be thankful for.

For updates and continued support visit David’s Go Fund me