Reintervention following stage 1 palliation: A report from the NPC-QIC Registry

Research Explained

Sinai C. Zyblewski, MD and Richard James, parent

Reintervention following stage 1 palliation: A report from the NPC-QIC Registry

Authors: Matthew W. Buelow, MD, Nancy Rudd, NP, Jena Tanem, NP, Pippa Simpson, PhD, Peter Bartz, MD, Garick Hill, MD

Published in Congenital Heart Disease 2018 Aug 10 [Epub ahead of print]

About this Study

Why is this study important?

Single ventricle heart disease with narrowing of the main artery where it leaves the heart (aortic arch hypoplasia) has high risk for medical complications and early death.

Problems with the heart after stage 1 surgery (residual lesions), are associated with prolonged hospital stays, longer time on life support, and early death

Some of the worst residual lesions are narrowing (coarctation) of the aorta and blockage of blood as it tries to leave the left atrium (atrial septal restriction).

These problems often need to be fixed with either catheter-based procedures or more surgery.

How was this study performed?

Data for patients who were already enrolled in the National Pediatric Cardiology Quality Improvement Collaborative (NPC-QIC) Registry were used analyzed.

Patients were included in the study if they had one of the two most common stage 1 surgeries (either a modified Blalock-Taussig (BT) or right ventricular to pulmonary artery (RV-PA) shunt), went home after that stage 1 surgery, and completed their stage 2 surgery or died between June 2008 and July 2014.

Centers that enrolled fewer than 10 patients into the NPC-QIC database were were not used in this study.

What this study tried to find out:

Describing what kinds of re-intervention procedures were used and how often they happened. Re-intervention was defined as catheter-based procedures and additional surgery between stage 1 and stage 2 surgeries.

Determining the risk factors for developing heart problems (residual lesions) after stage 1 surgery, and if the type of surgery made a difference (BT vs RV-PA).

Data about the patients’ medical history and hospital course were also collected.

What were the results of the research?

Study population characteristics

1156 patients were included in the study.

466 patients (40%) had a stage 1 surgery palliation with a BT shunt. 691 patients (60%) had a stage 1 surgery with an RV-PA shunt.

616 patients (53%) had a problem that was seen before the surgery (such as ECMO, metabolic acidosis, need for ventilator, kidney injury, arrhythmia, brain injury/seizures, need for cardiac catheterization).

869 patients (75%) had hypoplastic left heart syndrome and it was the most common diagnosis.

179 patients (15%) had a restrictive atrial septum prior to stage 1 surgery.

580 patients (50.2%) required more procedures after stage 1 surgery.

Re-intervention by shunt type

Of the 466 patients in the BT shunt group, 245 (52.5%) required more procedures.

Of the 691 patients in the RV-PA shunt group, 335 (48%) required more procedures.

The patients in the BT shunt group had more procedures than patients in the RV-PA shunt group (23% vs. 16%).

Between the stage 1 and stage 2 surgeries, there was no difference between the two groups in the need for extra procedures and surgeries.

Types and timing of re-intervention

Stage 1 hospitalization:

Patients with an RV-PA shunt needed fewer surgeries or catheter interventions to fix problems with the main artery compared to patients with a BT shunt (surgical aortic arch revision 0.002% vs. 2% and catheter-based aortic arch intervention 0.3% vs 3.6%).

However, patients with an RV-PA shunt had more shunt problems to fix with a catheter procedure compared to patients with a BT shunt (46% vs 27%).

Interstage period:

Patients with an RV-PA shunt had decreased risk of aortic arch surgical revision (5% vs 17%) and decreased risk of catheter-based aortic arch intervention (42% vs 59%) when compared to patients with a BT shunt.

Patients with an RV-PA shunt needed fewer surgeries on the shunt compared to patients with a BT shunt (5% vs 11%).

Patients with an RV-PA shunt needed more catheter-based interventions compared to patients with a BT shunt, including procedures on the shunt itself (20% vs 3%), on the pulmonary arteries (16% vs 5%), and on the aorto-pulmonary collaterals (32 vs 12%).

Stage 2 palliation:

At the time of stage 2 palliation, there were no significant differences in re-intervention between the shunt groups.

Risks for re-intervention

The presence of pre-operative arrhythmia or any other pre-operative risk factor were associated with reduced risk for having a re-intervention.

Being on a ventilator after an operation for more than 2 weeks was associated with the need for more procedures or surgery.

What are the limitations of this study?

Because of the limitations of studies that look at data from the past, this study was not able to see what directly caused the need for extra procedures and surgeries.

This study did not use higher risk patients who either died before they left the hospital or stayed in hospital until stage 2 surgery.

Specific reasons for re-intervention, exact timing of re-interventions, and complete pre- and post-intervention data were not collected.

This study was unable to find out how re-intervention affects risk for death.

The study was unable to find out if hospitals did procedures and medical care differently from each other.

What it all means

Between the first two main surgeries (stage 1 and stage 2), babies often need to have more procedures and surgery.

In this study, early re-intervention during the stage 1 hospitalization occurred more frequently in patients having a BT shunt. These interventions were usually surgeries and catheter procedures on the aorta.

Between the stage 1 and stage 2 surgeries, patients with a BT shunt more often had catheter-based and surgical interventions on the aorta. Patients with an RV-PA shunt had more catheter-based intervention on the shunt, pulmonary arteries, and aorto-pulmonary collaterals.

This study was unable to determine if re-intervention was due to poorly performed surgery, better detection of residual lesions, or more aggressive treatment of possible complications.

This study was unable to find out if a need for more surgery or procedures made a difference in whether a child lived or died.

Examining variation in interstage mortality rates across the National Pediatric Cardiology Quality Improvement Collaborative

Background

Founded in 2006, the National Pediatric Cardiology Quality Improvement Collaborative uses collaborative learning and quality improvement methods to improve outcomes for infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS). NPC-QIC recently reported a reduction in overall interstage (the time between stage 1 and stage 2 surgeries) mortality within the collaborative from 9.5% to 5.3% but it is not known whether there are differences in mortality across centers. The goals of this study were: 1) look at NPC-QIC center mortality rates and differences in ways different centers care for patients, and 2) compare individual patient characteristics, specifically high-risk patients, between lower and higher mortality centers to determine whether some centers care for lower risk patients.

Summary of What Was Done and What was Found

The investigators used the NPC-QIC registry to identify patients from participating centers that had more than 25 patients enrolled. The investigators defined “lower mortality centers” as those centers who had 25 babies in a row survive from the first stage discharge to the second stage admission. There were 7 lower mortality centers who had a total of 331 patients and an overall mortality rate of 2.7%. “Higher mortality centers” were defined as those with an overall mortality rate greater than 10%. There were 4 higher mortality centers with a total of 173 patients and an overall mortality rate of 13.3%. The main analysis compared lower and higher mortality centers’ baseline patient characteristics present at birth because of the potential for differences in center practices to affect later characteristics, such as need for a breathing tube before the first stage operation.

When the investigators looked at the baseline patient characteristics, the only difference between the groups was that postnatal diagnosis was less common in lower mortality centers (18.4%) as compared to higher mortality centers (31.8%). There were no differences in sex, race, ethnicity, gestational age, birth weight, primary and secondary cardiac diagnoses, or the presence of major genetic syndromes. To answer the question of whether the lower rates of postnatal diagnosis at lower mortality centers accounted for the difference in mortality as compared to the higher mortality centers, the investigators did a specific analysis. They still found that lower mortality centers had a lower rate after accounting for the difference in postnatal diagnosis rates.

When looking at characteristics that may be affected by center practices, the investigators found many differences. For preoperative characteristics, lower mortality centers had lower rates of breathing tubes, heart rhythm problems, and acidosis (marker of the heart and lungs not working well). When the investigators did the specific analysis to account for these differences between centers, lower mortality centers still had a lower mortality rate. There were many differences in operative and postoperative characteristics, such as type of stage 1 performed and time to extubation.

Limitations of the Study

All NPC-QIC studies have some limitations since not all centers participate in NPC-QIC, not all parents provide consent, and because errors in data entry are possible.

The definition of lower and higher mortality centers may be a coincidence of statistics rather than a true difference. Comparing center mortality rates is very difficult given the small number of HLHS babies at any one center and because interstage deaths are rare.

What it all means

This study showed that the difference in mortality rates between centers with lower mortality and centers with higher mortality does not seem to be due to differences in baseline patient characteristics or preoperative characteristics. Because the investigators found many differences in operative and postoperative characteristics, this difference in mortality may be due to differences in center practices starting in the operating room and continuing through discharge from stage 1. Future NPC-QIC studies could potentially answer these questions by focusing on differences in care delivery in the intensive care unit and operating room.

Fontan to Transplant: Building Teams for Transition

By: Kurt R. Schumacher, MD MS, Medical Director of the Pediatric Heart Transplant Program at the University of Michigan Congenital Heart Center at C.S. Mott Children's Hospital

Dr. Schumacher is the medical director of the pediatric heart transplant program at the University of Michigan Congenital Heart Center at C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital. Throughout his career, Dr. Schumacher’s clinical and research efforts have focused on understanding and improving the outcomes of heart failure and transplantation in children with congenital heart disease with an emphasis on Fontan patients. He is a leader of ACTION’s Fontan subcommittee aimed at improving the quality of care for all Fontan patients needing heart failure treatment and advance cardiac therapies, and he is a member of multiple national working groups aimed at improving outcomes for all single ventricle patients.

The relationship between a single ventricle family and their cardiologist is strong. From my perspective as a cardiologist, each patient requires a tremendous amount of thought and effort, but each patient can also give me with a wonderful sense of accomplishment. Through this single ventricle journey, we cardiologists become attached and even bonded to our families. We go through so many events together – hospital admissions, clinic visits, inter-stage monitoring, nerve-wracking surgeries, challenging recoveries, and joyful discharges. In my experience, the bonds formed during this process are often amazing and powerful. After the Fontan, we get to be there with our families watching children grow up. For a pediatric cardiologist, this is the ultimate reward. The reality is, however, that the path ahead is far from clear. We now know that growing up as a Fontan is accompanied by new challenges for both families and cardiologists. As much as we don’t like to think about it, a large proportion of Fontan patients will eventually need to be seen by a heart failure specialist, and many will need a heart transplant. Single ventricle congenital heart disease is now the leading indication for pediatric heart transplant evaluation. Like it or not, the reality is that sometimes pediatric transplant cardiologists are going to be a part of the Fontan patient’s care team.

Unfortunately, the approach of building a Fontan care team that includes a transplant cardiologist is not widespread. More often, patients and families are “referred for transplant evaluation” and find themselves with a completely new cardiologist who is now overseeing all of their care. Suddenly, the cardiologist (and team) that has seen this patient through all the clinic visits, surgeries, and hospitalizations is no longer “in-charge” and all new people are making the decisions. Some patients even need to transition their care to a completely new center. To make matters even more challenging, all of this change occurs at a time when anxiety about patient health is extremely high. As a pediatric heart failure and transplant specialist, I know from discussions with many patients that this transition can be a jolting and traumatic experience.

Why does this happen? It probably stems from many causes. Given the strong bonds they have, longtime cardiologists understandably don’t want to give up care of their patient so they delay their referral. Similarly, patients and families (appropriately) don’t want to leave their cardiologist, and they may not even understand that heart failure can occur after Fontan or don’t want to acknowledge that possibility. Finally, in our field, there are no formal recommendations for when to refer a Fontan for heart failure consultation. General cardiologists are left to decide on their own without guidance about what an appropriate Fontan heart failure consult is. This is a gap in our field that needs to be filled because a sudden transition in patient care is not the way it has to be. Early consultation from a heart failure/transplant expert would allow us to build Fontan care teams and eliminate the jolting change in providers.

ACTION (Advanced Cardiac Therapies Improving Outcomes Network) is a collaborative group of pediatric heart failure and transplant cardiologists and cardiac surgeons who are working to improve the quality of care that pediatric heart failure patients receive. When ACTION surveyed heart failure providers, a large majority wished that Fontan patients were referred earlier than they typically are. When we explored this finding, there was a clear desire for the patient and family, the primary cardiologist, and the heart failure/transplant cardiologist to be a decision-making care team prior to needing a transplant. Early referral of a Fontan patient for consultation from a heart failure cardiologist would allow the creation of this Fontan advanced care team. The heart failure cardiologist’s perspective and insights, including issues specific to potential future transplant, could be paired with the primary cardiologist and family’s experiences to collaboratively structure medical care plans for the patient. I strongly believe this could improve outcomes for patients. And should the time ever arrive that heart transplant is indicated, the patient and family wouldn’t suddenly be meeting a completely new team – that relationship is already established.

So how do we make this happen? ACTION is building a set of Fontan-patient-specific reasons that should prompt consideration of a referral to a pediatric heart failure specialist. These are based on the experiences and challenges that we have had with Fontan patients undergoing heart transplant. They allow us to meet patients before transplant is urgently needed (or even worse, before a patient becomes too sick for transplant). It will give us time to treat different types of Fontan failure and insure that a patient is as healthy as possible prior to undergoing transplant. It is our hope that by clearly stating these reasons, we will improve the timeliness of patient referrals, improve outcomes, allow the formation of a collaborative care teams, and eliminate the abrupt transfer of care that can be so difficult for both patients and providers. We welcome feedback and insights from patients and families as this effort moves forward. We all share the same goal – the highest possible quality of life for our children.

Helping siblings adjust, cope, and thrive

By: Caitlin Meehan, CCLS, Child Life Specialist at Nemours Cardiac Center Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children

Caitlin Meehan, CCLS

Child Life Specialist

Nemours Cardiac Center

Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children

When families learn that their child has HLHS, a variety of tasks are set in motion. Echocardiograms are scheduled; surgeries are discussed and planned. Parents research outcomes and what to expect for the future, and meet the lineup of staff who will help them along the way.

A diagnosis of HLHS affects the entire family unit, and often overlooked are the siblings of these newly diagnosed patients. What is the best way to describe HLHS and upcoming surgeries to these healthy siblings? How can we help them cope with the hospitalizations and surgeries that are coming? How can parents manage the unique needs of their child with HLHS, while still attending to their other children?

As a Certified Child Life Specialist in a cardiac center, I meet with families prenatally or shortly after birth to address these questions and many others. Parents often wonder how much information they should give to their other children, how to answer questions, and what to expect along the way. By addressing their needs prior to, during, and after hospitalizations, we can assure siblings of HLHS patients can not only cope with this diagnosis, but thrive in spite of it.

Finding the right words

Since an HLHS diagnosis can be shocking for a family, many parents feel like they should hide this from other children, or simply avoid telling them because they do not know what to say. Children tend to know when adults are hiding something from them though, and an absence of information can leave them feeling deceived or confused. They will likely notice subtle differences in routine or parents’ behavior, and eventually have more obvious questions like why their new brother or sister has yet to come home from the hospital. While it is not necessary to give all of the information possible, and it is certainly acceptable to convey uncertainty, it is essential that parents do not pretend as if nothing is wrong. A child who feels lied to may have trouble trusting his or her parent in the future. When speaking to children about their brother or sister’s diagnosis, it is best to use simple, honest, and concrete language to avoid misconceptions. Many attempts to “sugar coat” the conversation can actually lead to confusion and fear in the children hearing this. For example, avoid using words like “sick” as this may lead to additional fears when someone contracts a cold or virus, and this word tends to imply the patient is contagious. I explain that while growing in mommy’s tummy, little brother or sister’s heart did not grow the way yours and mine did and is not working the same. I explain that the heart is a very important part of the body, and he/she will need doctors to fix it before coming home and keep fixing it as he/she grows up. Older kids may worry and should be assured that their brother or sister will not be scared or in pain thanks to very special medicines.

Helping siblings cope with separation

One of the biggest concerns parents have is the potential separation from the non-hospitalized child. Often this child is, by necessity, left at home and cared for by other family members. It can be difficult for them to be away from parents and in unfamiliar settings. Parents can help by reassuring them that they are loved, they are safe, and they have done nothing wrong. Young children think very egocentrically and for this reason, they tend to think their thoughts or actions have an effect on how the world functions. Siblings may feel like they caused their brother or sister’s heart condition or that their parents are sad or scared because of something they did. In my interactions with siblings of new babies with HLHS and other congenital heart defects, I have heard a variety of misconceptions. One little girl thought her brother had a heart defect because she hugged her mom too tight while pregnant. Another boy thought it was because he had a cold and was around his pregnant mom. When we inform kids of what is going on we are also informing them of what is not, and that they, and no one, is to blame for this diagnosis.

Another way to help the non-hospitalized child is by helping them feel connected to their sibling and parents while they are away. For various reasons, visiting might be unfeasible or limited, so using technology and different activities can help bridge the distance. Routine phone calls or video chats such as before school or at bedtime may provide relief during what are typically difficult transitions. Social stories and homemade picture books use pictures to illustrate information such as a sequence of events, what is going to happen, and why. These can help younger children or those with special needs know where parents are, and more importantly, that they will come back. Siblings, especially those who are older, love taking on a caring role, so involving them in care and offering opportunities for control may help them cope. If the hospitalization is planned, brothers or sisters can help pack, can select favorite blankets or toys, or even decorations for the room so a little piece of them is in the hospital with the family. Likewise, having a keepsake from a parent or the hospitalized child can help provide comfort and help siblings cope with separation. When siblings are able to visit, I offer opportunities to make family portraits with hand/footprints, take family pictures, or provide scrapbooking items so siblings have something to take home. This is also as a way to document this special time.

Preparing siblings to visit the hospital

The topic parent ask me about most often are siblings visiting an intensive care unit or hospital in general. Parents do not want to scare or upset children by exposing them to breathing tubes, central lines, ventilators, etc. My advice is to follow the lead of your child when considering a visit. Do you have a fearful, anxious child? Do new situations or surroundings tend to frighten or overwhelm him/her? Or, is this child a little calmer and logical, adapting well to change? Is he or she persistent in asking to visit? Ask yourself, are the fears of bringing in the other child more related to your own fears, or what this child has expressed? Most children’s hospitals have personnel and resources to help prepare siblings for hospital visits, as well as educate, support, and occupy them once they are there. The medical team can put you in contact with a Child Life Specialist or Social Worker who is trained specifically to help your other children understand, know what to expect, and feel comfortable in this far-from-normal environment. As you know, children have very creative imaginations and for this reason, the fear of the unknown is likely more intense than a specific machine or tube. In my experience, most siblings are picturing circumstances far worse than reality, and when properly prepared for even a brief visit, we can put their minds at ease. This is certainly not the case across the board, and you know best if a visit is too much for your child. However, know that there are many resources to help facilitate this, and often it can bring many benefits to the non-hospitalized child.

Attending to the needs of siblings

Both in the hospital and back at home, it can be difficult to divide your time and energy among your children, especially when your child with HLHS requires so much attention. It is common for healthy siblings to exhibit attention seeking behaviors as they navigate these waters. Regression, jealousy, sleep troubles, and difficulty with separation are normal reactions and should subside with time on their own. If over time, this escalates to serious behaviors such as violence, excessive anger, or depression, a visit to a mental health care professional can offer more focused treatment. Formal and informal support groups for siblings and families can be helpful for some children, as they offer a space to safely share feelings and connect them with peers in similar circumstances. When possible, provide dedicated one-on-one time to the healthy sibling. This may not be easy for many families depending on circumstances, but even brief check ins where this child is the focus will have great benefits. This can be as simple as a special dinner or a walk in the park. The goal of these is not to distract your other children or cheer them up, but rather to make them feel special and allow them to express feelings, worries, and have their concerns validated if need be.

HLHS affects the entire family; this is unavoidable. However, with age appropriate explanations, inclusive activities, and special attention, siblings can grow into resilient and well-adjusted individuals. In fact, children whose siblings have a chronic condition such as HLHS have the opportunity to show more independence and maturity, and even become more compassionate and accepting teenagers and adults.

*Parents have granted written permission for use of all photos.

Practitioner's Perspective: Family Centered Care

by Michael V. DiMaria, M.D.

Children's Hospital Colorado

Family centered rounds have been introduced in many children’s hospitals for several reasons, but one of the primary motives is that families like to be involved in the health care decisions of their children. Family centered rounds are also a manifestation of a change in the culture of medicine, which has occurred relatively quickly. The way we as physicians practice medicine has shifted from what was a more paternalistic model to a cooperative one; this is addressed very explicitly in medical school curricula: we are in the era of ‘patient autonomy In pediatrics this translates into ‘family autonomy.’ The consequence of the rapid change is that both health care provider and patients can be unfamiliar with the process, and unsure of how to make best use of this opportunity.

To understand what this means for families, let’s start by talking about what to expect on morning rounds. First thing in the morning, after the incoming team of providers has gotten up to speed on developments from the overnight shift, the group gathers at each patient’s bedside in turn. The goal will be to review the events of the last day, discuss how the patient is doing, and come up with the plan for the next day. This is an important time for everyone on the medical team and the family to get on the same page. Often times, especially at a teaching hospital, a large crowd will be present. In order to make things flow more quickly and easily, the attending may ask that any questions or concerns be raised at the end of the presentation; it is difficult for the team to stay focused and efficient if there are frequent side conversations.

Next, the players: the patient’s nurse will be at the bedside, advocating for the family, bringing up unresolved issues, and clarifying his role in the plan. A resident or fellow will ‘present’ the patient to the group, meaning that she will be responsible for knowing all the details about the patient and summarizing them efficiently to the group. To briefly explain how she came to be in this position, after graduating from medical school and receiving an M.D., she did a 1 year internship, then began a 2-5 year residency; after residency, she may do an additional 3-4 years of training, called a ‘fellowship’ to sub-specialize. After finishing all of her training, a doctor becomes an ‘attending physician’ – the person in charge of the team. The attending will be listening, teaching, and guiding the trainee through the process of assembling the data and figuring out what to do next. Various other people may be present, including pharmacists, nutritionists, nursing leadership, physical therapists, etc.

As alluded to above, rounds will consist of a brief description of the day’s events, a review of the physical exam, then a bunch of numbers (lab values, fluid intake and output, ventilator settings, etc.). At the end of all of this comes the assessment and plan. It goes without saying that during the assessment the presenter verbalizes their impression of how the patient is doing. The plan is usually presented in parts, according to ‘organ systems’ (all of the respiratory issues are grouped together, as are all of the cardiovascular problems, etc). This will sound something like, “From a respiratory standpoint, I think we can try to decrease the oxygen from 2 to 0.5 liters per minute. From a nutritional standpoint, I think that Sam can try to eat a solid diet today…” This will continue until all of the active medical issues have been addressed.

When patients and care providers first encounter family centered rounds, some may find it uncomfortable to have conversations about sensitive topics in the presence of a large group. Of course, there should always be the option for the family to have a more private conversation with only the essential members of the team, should there be concerns about privacy. From the resident’s perspective, my colleagues and I were initially very nervous about presenting a patient history and physical in front of the patient’s family as a resident. Aside from being a little shy, I think I was nervous that I would get something wrong and that the family would correct me in front of the boss. I quickly got over this fear, when it became obvious that the common goal was historical accuracy.

There are several points during the process when the family’s input will be especially helpful. It goes without saying that nobody knows a child better than the primary caregivers, and so who better to be the definitive source of historical information? Because team members may come and go twice a day (at the end of a 12 hour shift), none will have the perspective of the family, who will have been with the patient continuously. Being able to give the team an idea of the overall trend of the patient’s symptoms can be very helpful. Similarly, it can be difficult for people who don’t know the child to tell what sorts of behaviors are personality-related and which are indicators that things are not quite right.

The goal of this process is to get the patient home, feeling well, and able to participate in all of the things that go into being a healthy, happy kid. More often than not, this means that the family will need to continue some interventions in the home. So, part of having a child in the hospital is learning about the disease and the treatments. Being an informed caretaker will better enable the family members to identify when problems occur at home, and what to do about them. Some measure of our success as care providers is whether or not the family feels comfortable once they are discharged. Our hope is that the shared knowledge and unified goals of families and care providers results in a close working relationship that develops in this setting of family centered care.Thank you, Dr. DiMaria, for lending your insights and expertise to our HLHS families!

Thank you, Dr. DiMaria, for lending your insights and expertise to our HLHS families!

Parent Travel Scholarships - NPC-QIC 2017 Spring Learning Session!

Registration for the NPC-QIC 2017 Spring Learning Session is now open! Sisters by Heart and NPC-QIC want to send YOU to the Spring Learning Session May 18-20th 2017! Together, Sisters by Heart and NPC-QIC are once again offering parent travel scholarships, valued at $500 each, to four parents to attend the learning session in Cincinnati, OH. If you are new to the HLHS world, haven’t heard of NPC-QIC before, or have questions about what NPC-QIC does, we have put together some information for you.

The National Pediatric Cardiology Quality Improvement Collaborative’s mission is to improve the care and outcomes for children with cardiovascular disease. NPC-QIC’s current quality improvement project is working to improve survival and quality of life for infants with Hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS). The collaborative is made up of clinicians from fifty-eight (58) centers from across the country and parents of children needing a Norwood (i.e. HLHS).

Here is what some past travel scholarship families have had to say about the event:

"Attending the NPC-QIC Conference was rewarding at multiple levels: First, being in a room of cardiac professionals and parents who are focused and are driven to improve the care of our HLHS kids, and their families, touched my heart and made me further grateful for these dedicated people. I also appreciated hearing that the current Collaborative statistics (which are really good!) still aren't good enough for these professionals. Our kids are fiercely being fought for behind the scenes (as well as on the front lines) and that is incredible to see, first hand. Finally, this group allows their centers to be vulnerable for the sake of improving the HLHS outcomes and that is amazing!

I look forward to be a contributing part of the Collaborative efforts at future conferences and at our center, and hope to share the work being done to encourage and bring hope to newly diagnosed, and current, HLHS families in Colorado and surrounding areas.

Thank you so much Sisters-by-Heart for the opportunity to meet so many amazing people and to continue my efforts to help our center help more HLHS families! It was great to finally meet all of you, too!" - Erica Isakson

"As a Dad of a 3 year old (Roman) with HLHS, I would like to start off by thanking Sisters by Heart for the great opportunity to attend the fall 2014 learning session. Leading up to the learning session I was a little nervous it was going to be a bunch of healthcare professionals speaking in a langue I didn’t understand. Once I got there I realized I could not have been more wrong. The learning session featured individuals from about 50 centers which included doctors, nurses, and parents. They all come together for one common goal - Improving care for patients with HLHS and their families. I am not sure what I enjoyed more either participating in the learning session – or getting to interact with other parents of children with HLHS of all different ages.

During the learning session it was clear that the medical professionals really valued our opinions. I was asked several different questions while I was there ranging from time of diagnosis all the way up to his current care. I know all HLHS parents remember that moment when they find out their child has a life threatening condition. During the learning session we spent hours discussing what could have made the time after that moment better. We heard great examples of things to do, and horrible examples of what to avoid.

I also was excited to meet with parents of other children with HLHS. I was able to meet parents with children of all ages from babies to college students. Hearing their stories provided me great hope. Generally as a parent of HLHS you are always looking so short term; this was a good opportunity to look long term. I thought it was awesome to hear everyone’s stories, especially the ones about the older children.

One last aspect of the conference I wanted to mention was how great it was to see hospitals working together to better care. It would be really easy for the top hospitals to keep all there data in-house and not share it with other hospitals, but that does not happen with this group. All involved are excited and even eager to share their best practices and success stories.

I came away with great comfort knowing there are some many intelligent people who care so greatly about our children, and look forward to being able to attend future learning sessions." - Matt Ulrey Dad of Roman age 3

Parents with a single ventricle child, who required a Norwood or Norwood varient surgery may attend the learning session and/or apply for a travel scholarship. You do not need to be currently involved with your child's interstage clinic, however you are encouraged to reach out to your child's center prior to the learning session.

Sisters by Heart will be accepting travel scholarship entries until April 1st 2017. In order to be considered, please send an email with "Learning Session Scholarship" in the subject field to info@sistersbyheart.org with the following information:

Name

Address

HLHS child's name and DOB

HLHS child's hospital

Have you contacted your child's center to inquire about funding to attend the Learning Session?

A brief paragraph on why you would like to attend

If you are interested in attending and can make arrangements for childcare/time off work, please apply! This is such a wonderful opportunity to share your opinions, answer questions from a “professional” perspective as a parent, and most importantly be involved in helping to improve care for HLHS children.

Parents awarded scholarships will be responsible for making their own travel arrangements. If you have questions regarding the scholarship process, don't hesitate to email us at info@sistersbyheart.org.

If you're already planning on attending the learning session, please make sure to register for the event at NPC-QIC's website

We look forward to seeing you in Cincinnati in May!

On Finding His Tribe

When I was maybe 10 or 11, I read a book about a girl named Dawn, who had cancer. I remember her going to “Cancer Camp” and how much it meant to her to be around her peers, to feel “normal.” For some reason, the idea of that camp stuck with me. I just never knew how close it would hit to home with my own family years later.

My 6-year old son, Bodie, has Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome (along with a few other fun surprises). For the past almost 7 years, I have immersed myself in the “Heart Community.” I have made friends with other heart moms, some only virtually through social media, some only in person, and some that started virtually but eventually became in person relationships. In it, found MY tribe. It is full of amazing women with stories like mine, who have children like my son. Women who share my fears, and who talk me off of my anxiety ridden ledge at 2am. We are there for each other through this crazy journey.

I have introduced some of these women to my family, and we do things with the ones who live locally. My son, and his 9 year-old heart healthy sister, get to see other kids like them occasionally. I thought that was enough. I really did.

I was wrong.

MY tribe has been wonderful for me. But it hasn’t quite met the needs of my son and his sister. And I didn’t even realize it, until last weekend, when we went to our first Heart Camp. And then I saw it. The profound connections made between survivors. The look that simply says “I’ve been there. I get it.” The sense of comradery, of feeling “normal” in a world where their scars make them anything but. The overwhelming shared hope of seeing older survivors living amazing, authentic lives in spite of their very serious heart conditions.

Meeting up with a heart family here or there, or once a year at a Heart Picnic is wonderful. There is a very valuable space for that. But, honestly, there is a vast difference between a few hours spent with other heart families – and 72 hours straight spent immersed in the heart culture with tons of families (there were over 60 families at our camp!). It is difficult to even put into words what our weekend at Heart Camp meant to us as a family.

Perhaps the best way to explain it is to describe the most profound moment of the weekend for me. My sweet boy, at the tender age of 6, has just in the past 6 months or so started to become self-conscious about his scars. This summer, he has wanted to keep his rash guard on anytime he is swimming. On Saturday night, the camp was offering all sorts of fun activities, including tattoos and face painting. My son wanted to put a tattoo on his chest. But he wouldn’t take his shirt off. He asked me if we could just go to the bathroom and do it instead, and then started to make up all sorts of excuses for why he didn’t want to get the tattoo after all.

I was at my emotional wits’ end. Despite my reassurances that it was heart camp and he didn’t need to worry about his scars, he wouldn’t budge. I didn’t know how to help him. And then, something extraordinary happened. Our family had been assigned a mentor, an amazing teenager living with heart disease, to shadow us for the weekend. Our mentor was Kenny. When Kenny realized Bodie was struggling, he came over, took his shirt off to show his own scars, and began to talk to Bodie. Before I knew it, we were surrounded by 3 mentors, all teenage boys with their shirts off in the cold evening air, just to show my son that his scars weren’t anything to be ashamed of. And they were reassuring me that they, too, had all gone through it.

Kenny took Bodie a bit away from us to talk to him. I don’t know what their conversation entailed. All I know is that, in a very short period of time, my son had his shirt off and wanted to show me his scars and talk about how brave he was.

I know this is a journey, and this won’t be the last time we talk about my son’s scars. But last weekend was a valuable stepping stone in his journey to acceptance. And for that, I will be forever grateful. That moment would never have happened without heart camp. I love my son, and I support him in every way I can, but, at the end of the day, this is HIS journey, and I don’t know what it’s like to walk in HIS shoes. But his peers at Heart Camp do.

On Saturday morning of our camp, we had the opportunity to attend a Q&A panel with 12 of the teen mentors. Upon being asked what had helped ease their journeys the most, every single one of them recommended Heart Camp. And I don’t doubt it. The benefits are enormous. It was clear from looking at how close all of the teen mentors were that their experiences at Heart Camp had fundamentally shaped their views on their hearts and their futures. They were an exceptionally inspiring and tight knit group of young adults.

We are profoundly lucky in California, since we have 2 heart camps to choose from, Camp Taylor in Northern California (where our family was last weekend) and Camp del Corazon in Southern California (which starts at age 7). With a family camp for younger kids, and options for siblings to attend youth camp alongside the CHDer, Camp Taylor was the perfect choice for our family. And one that was absolutely worth every minute of the 5 hour drive there. Not every state has 2 options within driving distance. But there ARE camps across the United States. We at Sisters by Heart are working on compiling a list – if you know of one, please let us know so we can add it to our list! If you have a CHDer of school age, I could not encourage you enough to see whether there is a heart camp near you. We met one teen mentor who flew from Denver to California for Heart Camp each year. I promise, the experience your child gains will be 100% worth it!

Before heart camp, I had MY tribe. Last month at Heart Camp, our son found HIS tribe. One that he will walk with for the rest of his life. And for that, we are inexplicably grateful. As they so beautifully put it at Camp Taylor, heart camp is where "Kids Meet... Scars Blend... Wonders Happen!!!

NPC-QIC/SBH Response to HLHS Statistics Shared by the CDC

The numbers reported this week by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention do not represent the current state of outcomes for infants born with HLHS.

Last week the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) posted information about a study that has recently been published in the Journal of Pediatrics called Differences in Survival of United States Children with Birth Defects: A Population-Based Study.

Purpose: It is important to understand what question the researchers are attempting to answer when evaluating a research study and its results. The purpose of this particular study, which was performed by a group of researchers on behalf of the National Birth Defects Prevention Network, was to evaluate possible racial or ethnic differences in survival of children born in the United States with various birth defects, ranging from congenital heart defects (CHD) to gastrointestinal defects to neurologic defects. The purpose of this study was not to describe the current state of survival in the United States for any of these birth defects.

Methods: It is also critical to understand the methods that the researchers used to answer their question. These researchers chose to use a birth defect registry that was active in several states: Arizona, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Massachusetts, Michigan, Nebraska, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina and Texas. In fact, some of the states had incomplete information from parts of their state. For example, births from New York City were not included in the New York state information. Importantly for HLHS, the birth defect registry captures all live births, including those infants whose parents elected comfort care only.

All studies have limitations to their methods. In the case of this study, the authors note extensive limitations in their paper. Most published studies have ~1 paragraph describing the limitations; this paper includes 4 extensive paragraphs describing the limitations. Some of these limitations include possible misclassification of birth defects and potential misclassification of deaths. It is important to note again that the purpose of this study was not to describe the current state of survival in the United States for these birth defects. If these authors wanted to answer that question, they would need to use different methods and use more current survival information.

Results and comments: This paper has some important results. The researchers found that children with birth defects born between 1999-2007 to non-Hispanic black and Hispanic mothers have a lower survival rate than those born to mothers of other ethnicities. This was especially true for children born with CHD. We do not know if this is still true in infants born with these birth defects in 2015, but this result should give us pause and cause us to look at our systems of care to make sure we eliminate any ethnic disparities in outcomes in our babies with CHD. Unfortunately, the CDC did not focus on this important finding when posting the results of this study. Instead they focused on the mortality rates of various birth defects noted in this study. In our opinion, the CDC webpage is misleading as it emphasizes the mortality rates noted in this study rather than the results of the purpose of this study, the ethnic differences in mortality rates during that time period (1999-2007). This data does not reflect current mortality rates.

What is the current state of outcomes in infants born with Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome? The most accurate and up-to-date information about survival for infants born with HLHS comes from the Society for Thoracic Surgeons (STS) registry, the NPC-QIC registry, and publications that look at longer term survival. The STS tracks survival until hospital discharge for all patients who undergo surgery for congenital heart disease for nearly all centers performing these surgeries in the United States.

For the time period 2010-2013 there were 2177 Norwood procedures performed for HLHS at STS centers and there was an average survival to hospital discharge of 83% among all centers.

For the year 2013 there were 714 Norwood procedures performed in STS centers with a 85% survival rate to discharge.

For information about survival after hospital discharge, in the “interstage” period and beyond, we need to turn to the medical literature since STS only tracks survival to hospital discharge following surgical procedures. There have been several reports describing survival after discharge following the Norwood procedure.

The NPC-QIC registry historically has demonstrated interstage survival of ~90-92% and more recently (since January 2013), interstage survival in centers participating in the NPC-QIC collaborative is approaching 95%.

The Pediatric Heart Network Single Ventricle Reconstruction Trial enrolled infants with single ventricle between 2005 and 2008 and looked at two different surgical approaches to the Norwood procedure. This study enrolled 549 infants (not all of them had HLHS) and the survival rate to 1 year of age was ~73%. It is important to recognize that these patients were operated on and followed at 7 Pediatric Heart Network centers and that this study was started almost 10 years ago.

The National Pediatric Cardiology Quality Improvement Collaborative remains dedicated and committed to improving not only survival but also quality of life for children with HLHS and their families. While we recognize that we have a long way to go in our efforts, we have seen tremendous improvement in outcomes in HLHS in the past decade. The numbers reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention do not represent the current state of outcomes for infants born with HLHS, nor do they reflect the hard work done by caregivers and parents in improving outcomes for our patients.

Jeffrey Anderson, MD, MPH, MBA, Improvement Advisor and Research Committee Chair

Robert Beekman, MD, NPC-QIC Chair

Carole Lannon, MD, MPH, Improvement Design and Implementation Lead

Stacey Lihn, NPC-QIC Parent Lead and Sisters by Heart President

Laura E. Peterson, BSN, SM, Senior Quality Improvement Consultant

You’re the General Manager of Your Team

By Caleb Lihn

This is one of my favorite times of the year, I hate to admit it, but a major reason is because football season is hitting its stride. One of the things that forces me to pay such close attention to football is fantasy football. If you, or a family member, play fantasy football then you know all too well the phenomenon of the fantasy footballer in your house spending an inordinate amount of time on Sunday pouring over scores and statistics. You also probably understand that fantasy football is not particularly realistic of the actual game as it involves drafting several individual players and hoping that, as a collective, they play great games and score you a ton of points. I’ve noticed that some weeks my star players don’t perform very well but, despite that, their real life teams win the game. The reason for this is simple; one player doesn’t make the team or win the game. It takes a complete team performance to deliver a win. Teammates communicating, knowing and executing the plan, reacting to adverse conditions, and giving maximum effort.

Sports is often compared to life. Of course what to compare it to depends on our individual life experiences. As a heart parent, I’ve compared sports to the heart world. I’ve also compared it to war, but that’s a story (or battle) for another day. As heart parents, we’ve all experienced overnight and often lengthy hospital stays. It was during my daughter’s recovery from her second open heart surgery that I realized her care team in many ways is like a football team. From there, I consciously realized something that should be common sense, the outcome is dependent upon the performance of the whole team, not just a single member. While he never coached football, Phil Jackson, coached many basketball teams to NBA championships. He once said “the strength of the team is each individual member…the strength of each member is the team.”

I have no doubt that Coach Jackson applied his comments to sports, however, the very same could be said for your child’s care team or heart center. Think about it, everyone in your child’s center has their position and assignment, just like a football team.

There may be some debate about who is the quarterback, but it’s routinely stated that the most difficult position in sports is the quarterback position. If you’re an NFL fan, then you also know that without a good quarterback, your team stands little chance of success. Similarly, no heart center can function without their own quarterback, the cardio thoracic surgeon. A job also known to be one of the most difficult specialties in medicine. A team may seem more attractive or flashy if it has a good quarterback, but keep in mind the quarterback can’t do it alone. It takes a team to win.

Every team needs a head coach, someone to see the big picture and make sure the plan is implemented. In the heart world, the head coach is your child’s cardiologist.

The offensive lineman are the unsung heroes in the trenches, using their muscle to make the quarterback look good. The offensive lineman of the heart center are the intensivists.

The interventional cardiologists are the wide receivers on the team. They both require good hands, finesse, and taking precise routes.

In football, special teams are charged with helping the team maintain good field position. The special teamers in the heart center are the nurses. Nurses are tasked with maintaining our kids after a surgery, catheter, or unexpected setback. Special teams are a key component of any football team, just as the nurses are an integral part of the care team.

Quarterbacks need to be in sync with their center, the one responsible for snapping them the ball. They have to have a rhythm and excellent communication to execute a clean exchange of the football. The heart center’s quarterback, the surgeon, similarly relies on the anesthesiologist, requiring the same rhythm and communication for the best chance at success.

Most football teams have a nutritionist. The nutritionist is the running back of the heart center. They are given the play and told to carry the ball through a tight space. Their position is fully dependent on timing and capitalizing on the right window of opportunity.

Most importantly, every team needs a general manager – someone who decides who makes the team roster, takes in all the information, including recommendations from all members of the team, and has final say in ultimate decisions. The general manager of your child’s team is you. So next time you are in the huddle (i.e. interviewing care teams, in rounds, at the bedside) make sure you harness your inner GM and speak up, ask questions, and share concerns.

When deciding on the team that cares for your child, remember “the strength of the team is each individual member.” Choose a well balanced team, that is impressive at all positions, works together, communicates well, reacts favorably to adverse conditions, and gives maximum effort.

Assembling your team can be overwhelming, particularly for a family new to the heart community, however, like any other general manager, you need to learn to lean on your scouts. In this world, your scouts are the parents and families who’ve traveled this road before you, who’ve already assembled their team and taken on the opponent. Use your scouts, don’t hesitate to reach out to heart families via social media and support groups. By reviewing their game film you can hopefully improve the outcome of your child’s journey.

Caleb is father to 7-year-old Emerson and 5-year-old Zoe, who was diagnosed in utero with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. An in utero diagnosis provided early learning, including the importance of cardiac experience when treating and caring for complex CHDs. A second opinion led Caleb and his wife to the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia where Zoe underwent her three-staged palliation.

As you may have guessed, Caleb is also a fan of football and addicted to fantasy football (are four teams too many?). In his spare time, Caleb is an attorney in Phoenix, Arizona.

Interstage Site Care and Growth

Key Findings: Comparison of growth in Single-Ventricle infants followed for interstage care at surgical centers versus non-surgical centers

_________

Cardiology in the Young recently published a study online on January 2015: “Site of interstage outpatient care and growth after the Norwood operation”.

The NPC-QIC Research and Publication Committee has reviewed this article and a summary of the findings can be found below.

Main Finding from this Study:

Despite advances in surgical and medical care for infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome after the Norwood procedure, the interstage period remains a time of high risk. One major problem these children suffer is poor growth, which has been the focus of recent efforts for improvement. Specifically, specific practices to improve growth include: use of home weight scales, monitoring for weight loss or for adequate weight gain, standard feeding evaluation in the hospital after the Norwood procedure, regular phone contact with cardiology clinicians, and dieticians at clinic visits.

This study was a retrospective comparison of two groups: infants who received their outpatient interstage care and cardiology visits at cardiac surgery centers that performed their Norwood procedure, and infants who received outpatient interstage care and cardiology visits at other cardiology sites. The authors of this study concluded that regardless of where infants received outpatient interstage care, their growth over the interstage period did not differ and remained below-average.

About this study:

Why is this study important?

As mentioned above, infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome after the Norwood procedure are known to be at risk for poor growth, and our understanding of what specific practices are important to improve growth has advanced.Practices such as using home weight scales, maintaining regular phone contact with cardiology clinicians and dieticians, and monitoring for adequate weight gain are useful tools for families and cardiology care providers.However these practices require additional staff resources and equipment, and centers have been previously shown to vary in their use of these practices.

The authors of this paper hypothesized that infants who received outpatient interstage care at cardiac surgery centers would achieve better growth compared to infants who received care at other sites, since cardiac surgery centers are based in children’s hospitals with larger numbers of clinical staff.If either group of infants had poorer growth, then further measures (such as use of additional clinical staff or equipment) could be started to “close the gap” in growth.

How was this study performed?

This was a retrospective study of patients enrolled in the National Pediatric Cardiology Quality Improvement Collaborative single ventricle registry from 2008 to 2013. Infants who successfully completed the interstage period (from Norwood operation to stage 2 procedure) were included in the study, and infants were excluded if: the Stage 2 procedure was not completed due to cardiac transplantation or death before Stage 2, or if there was missing weight data.

The infants were classified into two groups, based on data collected from the registry: the surgical site (SS) group, who had all interstage care given at the same center where the Norwood procedure was performed; and the non-surgical site (NSS) group, who had some or all interstage care given at another center distinct from the primary surgical center.

What were the results of the research?

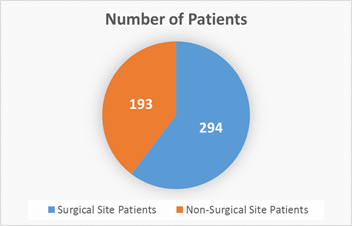

487 infants total were analyzed: 294 infants in surgical site (SS) group, 193 infants in non-surgical site (NSS) group.

By Norwood hospital discharge, infants in both groups were similar except that the SS group were less likely to have hypoplastic left heart syndrome, and were slightly older at Norwood hospital discharge.

Specifically in terms of growth, infants in both groups had similar weight-for-age z-scores (a statistical measure for normal values of growth for a specific age).

By the end of the interstage period, infants in both groups had similar weights (including similar weight-for-age z-scores). When looking at other measures of growth such as average weight gain per day, there were also no differences between the two groups.

When looking at all infants included in the study, the authors found that 29% were severely underweight (had very low weight-for-age z-scores) by stage 2 procedure.

Average daily weight gain during the interstage period was also not different between the two groups – 22.4 ± 6.4 g/day in the surgical site group versus 22.7 ± 6.3 g/day in the non-surgical site group (p =0.61).

What are the limitations of this study?

This was a retrospective study using data from a national database, and some patients (20% of infants enrolled) could not be included in the study due to inadequate or missing data. Although this study included patients from many cardiac centers in North America, it may not be representative of outcomes for patients at other centers.

The authors compared two groups of patients in this study: infants who had interstage care given only at the center where their surgery was performed, and those who had interstage care given at another site. Infants who had some care given at both sites were included in the non-surgical site group, but may have variable involvement of the surgery center team (including dieticians, etc.). The authors state these details were not defined further in the database (and thus could not be evaluated further), but were able to show no difference between groups in use of home weight scales or monitoring for interstage growth “red flags.”

What are the takeaway messages considering the results and limitations of this study?

For infants after the Norwood procedure, weight gain during the interstage period is not affected by the site of interstage outpatient care. However, a significant amount (nearly one-third) of infants studied were severely underweight by their stage 2 palliation surgery. Previous studies have demonstrated that specific practices, such as use of home weight scales and regular phone contact with cardiology clinicians/dieticians, are associated with improved weight gain in those infants who receive it. Current efforts through the NPC-QIC are underway to reduce variation and increase use of these practices.

Patel MD, Uzark K, Yu S, Donohue J, Pasquali SK, Schidlow D, Brown DW, Gelehrter S. Site of interstage outpatient care and growth after the Norwood operation. Cardiol Young. 2015 Jan 2:1-8.

Hope for Superheroes: Fontan care packages!

Four years ago, Sisters by Heart was born out of a mission to provide support and hope to newly diagnosed HLHS families. We are well known for our signature Norwood care packages, which include all the essentials a family needs to support a newborn child in the hospital recovering from open-heart surgery – and most importantly, HOPE! We have loved supporting newly diagnosed families as they have begun their journeys and joined our heart family.

But we wanted to do more, to branch out, to provide even more support to the families we love and serve. And so the “Fontan care package” idea was born. Our Board has been hard at work over the past year deciding on the perfect items to include in a care package for a toddler or preschooler recovering from open-heart surgery. We wanted to include items to empower a young child and his or her family, and to pay homage to just how strong these kids are, and just how far they’ve come. And, of course, to give our customary dose of HOPE!

We’re thrilled to announce today is our official launch date for our Fontan superhero care packages!

Before we launched, we needed someone to test out our care package, to make sure it was just right. We were thrilled to have that recipient be this cutie, Kate.

Kate has had a particularly rough go of it, including an ecmo run and a Glenn takedown. She likes to give her medical team a run for their money and it is no small feat that she has arrived at the Fontan. Her family received a Norwood care package when her mother was still pregnant with Kate. And her amazing mama, Erica, is well known and well loved by our board. So there was no question that she was our perfect first recipient!

Our Fontan superhero care packages include a super-Fontan cape and mask, a coloring book specially designed just for SBH and crayons, a hospital gown, silicone bracelets for mom, dad and HLHSer, stickers for siblings and, from time to time, a few extra goodies! And it’s all wrapped up in a cool Fontan superhero drawstring backpack!

U.S. News & World Report Rankings Explained

By: Dr. Jeffrey Anderson, Pediatric Cardiologist at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC)

Dr. Anderson has been a pediatric cardiologist in the Heart Institute at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) since 2009. He is a graduate of the University of Utah School of Medicine and recently completed a Masters in Business Administration at the Ross School of Business at the University of Michigan. Dr. Anderson completed his pediatrics residency at the University of North Carolina Children’s Hospital before coming to CCHMC, where he finished his training in Pediatric Cardiology and advanced training in Pediatric Electrophysiology. He currently leads quality improvement and value efforts within the Heart Institute as co-director of the Heart Institute Safety, Quality and Value program. Nationally, Dr. Anderson holds several leadership positions including roles with the National Pediatric Cardiology Quality Improvement Collaborative and the American College of Cardiology.

Each spring the U.S. News & World Report releases their rankings of the best medical centers and clinical programs in the United States. The purpose of these rankings, as noted by the U.S. News & World Report is to “identify the best medical centers in various specialties for the most difficult patients”. Because the methods used by the U.S. News & World Report are complex, understanding and interpreting the rankings can be difficult for patients and families. This post is meant to help families understand some of the detail that goes into these rankings and give some guidance to interpreting them as you make decisions about your child’s care.

History of the U.S. News & World Report rankings

The following is taken directly from the 2015-2016 US News & World Methodology Report (http://www.usnews.com/pubfiles/2014_BCH_methodology_report.pdf). It is important to note that the U.S. News & World Report ranking for Pediatrics initially was entirely based on a reputational survey of physicians. Between 2007 and 2015 the reliance on reputation has decreased and the report has been more and more heavily based on outcomes, providing evidence-based processes of care, and structural (e.g. provider certification, presence of specific programs) elements. In 2015, the Pediatric subspecialty rankings still included a reputational survey, but this survey was only weighted at 16.7% of the total score. While the U.S. News & World rankings are still not perfect, each year additional outcomes measures have been added and the overall methodology continues to improve.

In 1990, U.S. News & World Report began publishing what was then called America’s Best Hospitals. The intent was to identify the best medical centers in various specialties for the most difficult patients − those whose illnesses pose unusual challenges because of underlying conditions, procedure difficulty or other medical issues that add significant risk.

The 2014-15 rankings mark the 25th year of annual publication. The focus on identifying top sources of care for the most difficult patients remains the same.

Pediatrics was among the original specialties in which hospitals were ranked, but until 2007 the pediatric rankings were based entirely on a reputational survey of physicians. Still, hard data to inform the rankings remained absent. Such data are critical because young patients present special challenges. Their small size relative to adults complicates every facet of care, from intubation to drug dosages; they are more vulnerable to infection; they depend on adults to manage and administer their medications, and they are treated for congenital diseases such as spina bifida and cystic fibrosis.

In the absence of databases for pediatrics comparable to MedPAR for Medicare recipients, U.S. News resolved to collect data directly from children’s hospitals. The first rankings that incorporated such data were published in 2007. Those rankings listed the top 30 children’s centers only in General Pediatrics. Data collection was subsequently broadened and deepened, and Best Children’s Hospitals now ranks the top 50 centers in 10 specialties: Cancer, Cardiology & Heart Surgery, Diabetes & Endocrinology, Gastroenterology & GI Surgery, Neonatology, Nephrology, Neurology & Neurosurgery, Orthopedics, Pulmonology and Urology.

The survey uses the framework developed in the 1960’s by Avedis Donabedian, conceptually defining the quality of healthcare using a structure, process and outcome framework. This framework is at the heart of many healthcare quality improvement initiatives and is based on the interrelationship of three key elements:

Structure: Indirect quality-of-care measures related to a physical setting and resources. Examples include staffing ratios, certifications, and patient volume.

Process: Measures that evaluate the method or process by which care is delivered, including both technical and interpersonal components. Examples include providing evidence-based care such as microalbumin screening for children with diabetes, and timely care delivery such as the timing of antibiotic administration for immunocompromised children with fever. Also included in this section is reputation with pediatric specialists.

Outcomes: Outcome elements describe valued results related to lengthening life, relieving pain, reducing disabilities, and optimal performance on disease-specific measures. Examples include bloodstream infections, survival after organ transplantation, and survival after complex heart surgeries.

Where does the information come from that determines the U.S. News & World Report rankings for Cardiology and who decides what questions to ask?

Information that is used to determine U.S. News & World Report rankings comes from two sources: 1) a survey that is completed and submitted by participating hospitals s and 2) a reputational survey that is sent to pediatric cardiologists and pediatric cardiac surgeon. Each year, programs are asked to submit data that are used to determine the rankings

Outcomes at the program (33% of the score)

Surgical mortality for various levels of complexity (STAT 1-5).*

Survival to first birthday after Norwood or hybrid Stage I palliation.*

One and three year survival after heart transplantation.

Prevention of ICU infections and pressure ulcers.

Processes at the program (16.7% of the score)

Does the program’s hospital use appropriate infection prevention measures?

Does the program formally monitor for surgical site infections?

Does the program have a single ventricle interstage monitoring program?

Does the program refer complex congenital heart patients for neurodevelopmental evaluation and intervention?

Does the program participate in known safety control measures?

Does the program participate in national registry and improvement collaboratives (NPC-QIC, IMPACT, STS, PHN)?

Structure of the program (33% of the score)

What is the surgical volume of the program for various levels of complex surgery (STAT 2-5)?*

What is the catheter procedural volume of the program?

Does the program have a cardiology and cardiac surgery fellowship?

Does the program have a cardiac transplant program?

Does the program have full-time subspecialists available (cardiac intensivists, cardiac anesthesiologists, adult congenital heart specialists?

Does the program have adequate nursing coverage?

Is the program committed to quality improvement and clinical research?

Is the program committed to engaging families?

* It is important to note that the surgical volume and outcome measures cover a four year period and lag for one year in the U.S. News & World Report rankings. For example, in the 2015 report surgical data from calendar year 2010-2013 was used to determine surgical volume and outcomes.

Reputation of the program (16.7%)

Each year a survey is sent to practicing pediatric cardiologists and pediatric cardiac surgeons. This survey asks participants to list 10 U.S. hospitals that they believe “provide the best care in Pediatric Cardiology for patients who have the most challenging conditions or who need particularly difficult procedures”.

The average of the previous four years of responses is used to score this part of the ranking. For example, in the 2015 survey the responses from 2012-2015 were used to determine the reputation score.

A question raised over the years has been the absence of patient and family experience scores as part of the rankings. This is obviously an important component of quality with patient/family responses providing a well-rounded and different perspective from which to inform improvement. Nationally standardized patient experience tools do exist for Pediatrics. Despite this, the tools are not broadly implemented across all reporting hospitals. Because of this variation, the ability to use these scores as part of a ranking methodology is not possible. Currently, hospitals are free to select the tool and method that best meets their informational and improvement needs. As long as this situation remains and hospitals are not required to report using a specific instrument, the use of patient and family experience performance data will not work for the rankings.

Continuous Survey Improvement

Each year, The U.S. News & World Report organizes a committee of pediatric specialists who review survey content and measures and make recommendations for improvement. This process helps ensure cross-hospital representation and involves content experts in the deliberations around measure selection and definitions. Although core outcomes that are nationally reported elsewhere (i.e. STAT survival) remain on the survey from year to year, changes that occur through this process can make year to year comparisons somewhat difficult. The makeup of the committee determining these questions not released by U.S. News & World Report. Each year, clinical programs are asked for input to improve the questions and that input may or may not be used to make changes the following year.

So how do I interpret and use these rankings?

First, there are problems with any system that attempts to compare clinical programs and rank them, the U.S. News & World Report is no exception. However, the U.S. News & World Report has made efforts over the last several years to place more of a focus on outcomes than on reputation. In addition, it is important that we have some way for parents and families to make informed decisions about programs and currently, the U.S. News & World Report provides a platform for this comparison.

One of the challenges with the U.S. News & World Report is the fact that much of the data, especially data about processes and structure of the programs, are self-reported. While the U.S. News & World Report does have the right to audit programs to determine the validity of their data, this is not a common occurrence. Another consideration is the lag associated with surgical volume and outcome data. Because the rankings use data from a four-year period ending the year prior, changes and improvement in the surgical program will not be reflected through the data for quite some time.

Despite the challenges described, the U.S. News & World Report rankings is a great way to begin the conversation about quality. After all, getting started is often the most difficult step. From that point, continued momentum for improvement around common measures that matter to patients and families can follow. If nationally standardized quality measures for a specific specialty or condition exist, then it is important that these measures be reflected in the survey. Viewed from this perspective, the survey becomes a way to both reinforce and make visible, quality measures that truly matter and make a difference in the lives’ of patients and families. Above all, probably the most important thing when using the U.S. News & World Report to make decisions about your child’s care, is that it serves as an important way to begin and continue the conversation about quality. From there, discussions with your cardiologist or cardiac surgeon about the structure and outcomes of the program at their center can continue, and then segue to a transparent conversation about program outcomes and efforts in place to continually improve.

Parents as Partners…. The long journey to true transparency.

By: Bambi Alexander-Banys, Nurse Practitioner

Bambi Alexander-Banys worked in pediatric psychiatric emergency and the neonatal intensive care unit before graduating with her Masters of Science in Nursing from Boston College. Commited to education as well as practice, Ms. Alexander-Banys began teaching in 2001 and maintained an adjunct faculty position for over ten years. She provided outpatient care to disadvantaged youth and owned her own concierge practice in Silicon Valley before joining the inpatient cardiology team at Lucile Packard Children's Hospital (LPCH) at Stanford where, in addition to providing inpatient clinical care, she manages the single ventricle Interstage Home Monitoring Program.