Interstage Site Care and Growth

Key Findings: Comparison of growth in Single-Ventricle infants followed for interstage care at surgical centers versus non-surgical centers

_________

Cardiology in the Young recently published a study online on January 2015: “Site of interstage outpatient care and growth after the Norwood operation”.

The NPC-QIC Research and Publication Committee has reviewed this article and a summary of the findings can be found below.

Main Finding from this Study:

Despite advances in surgical and medical care for infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome after the Norwood procedure, the interstage period remains a time of high risk. One major problem these children suffer is poor growth, which has been the focus of recent efforts for improvement. Specifically, specific practices to improve growth include: use of home weight scales, monitoring for weight loss or for adequate weight gain, standard feeding evaluation in the hospital after the Norwood procedure, regular phone contact with cardiology clinicians, and dieticians at clinic visits.

This study was a retrospective comparison of two groups: infants who received their outpatient interstage care and cardiology visits at cardiac surgery centers that performed their Norwood procedure, and infants who received outpatient interstage care and cardiology visits at other cardiology sites. The authors of this study concluded that regardless of where infants received outpatient interstage care, their growth over the interstage period did not differ and remained below-average.

About this study:

Why is this study important?

As mentioned above, infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome after the Norwood procedure are known to be at risk for poor growth, and our understanding of what specific practices are important to improve growth has advanced.Practices such as using home weight scales, maintaining regular phone contact with cardiology clinicians and dieticians, and monitoring for adequate weight gain are useful tools for families and cardiology care providers.However these practices require additional staff resources and equipment, and centers have been previously shown to vary in their use of these practices.

The authors of this paper hypothesized that infants who received outpatient interstage care at cardiac surgery centers would achieve better growth compared to infants who received care at other sites, since cardiac surgery centers are based in children’s hospitals with larger numbers of clinical staff.If either group of infants had poorer growth, then further measures (such as use of additional clinical staff or equipment) could be started to “close the gap” in growth.

How was this study performed?

This was a retrospective study of patients enrolled in the National Pediatric Cardiology Quality Improvement Collaborative single ventricle registry from 2008 to 2013. Infants who successfully completed the interstage period (from Norwood operation to stage 2 procedure) were included in the study, and infants were excluded if: the Stage 2 procedure was not completed due to cardiac transplantation or death before Stage 2, or if there was missing weight data.

The infants were classified into two groups, based on data collected from the registry: the surgical site (SS) group, who had all interstage care given at the same center where the Norwood procedure was performed; and the non-surgical site (NSS) group, who had some or all interstage care given at another center distinct from the primary surgical center.

What were the results of the research?

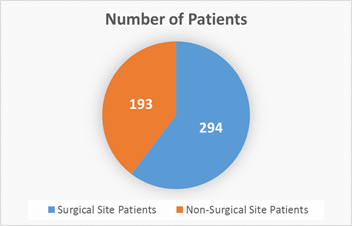

487 infants total were analyzed: 294 infants in surgical site (SS) group, 193 infants in non-surgical site (NSS) group.

By Norwood hospital discharge, infants in both groups were similar except that the SS group were less likely to have hypoplastic left heart syndrome, and were slightly older at Norwood hospital discharge.

Specifically in terms of growth, infants in both groups had similar weight-for-age z-scores (a statistical measure for normal values of growth for a specific age).

By the end of the interstage period, infants in both groups had similar weights (including similar weight-for-age z-scores). When looking at other measures of growth such as average weight gain per day, there were also no differences between the two groups.

When looking at all infants included in the study, the authors found that 29% were severely underweight (had very low weight-for-age z-scores) by stage 2 procedure.

Average daily weight gain during the interstage period was also not different between the two groups – 22.4 ± 6.4 g/day in the surgical site group versus 22.7 ± 6.3 g/day in the non-surgical site group (p =0.61).

What are the limitations of this study?

This was a retrospective study using data from a national database, and some patients (20% of infants enrolled) could not be included in the study due to inadequate or missing data. Although this study included patients from many cardiac centers in North America, it may not be representative of outcomes for patients at other centers.

The authors compared two groups of patients in this study: infants who had interstage care given only at the center where their surgery was performed, and those who had interstage care given at another site. Infants who had some care given at both sites were included in the non-surgical site group, but may have variable involvement of the surgery center team (including dieticians, etc.). The authors state these details were not defined further in the database (and thus could not be evaluated further), but were able to show no difference between groups in use of home weight scales or monitoring for interstage growth “red flags.”

What are the takeaway messages considering the results and limitations of this study?

For infants after the Norwood procedure, weight gain during the interstage period is not affected by the site of interstage outpatient care. However, a significant amount (nearly one-third) of infants studied were severely underweight by their stage 2 palliation surgery. Previous studies have demonstrated that specific practices, such as use of home weight scales and regular phone contact with cardiology clinicians/dieticians, are associated with improved weight gain in those infants who receive it. Current efforts through the NPC-QIC are underway to reduce variation and increase use of these practices.

Patel MD, Uzark K, Yu S, Donohue J, Pasquali SK, Schidlow D, Brown DW, Gelehrter S. Site of interstage outpatient care and growth after the Norwood operation. Cardiol Young. 2015 Jan 2:1-8.

Interstage Care and Mortality (surgical v. non-surgical sites)

Special thanks to Dr. David Schidlow

The journal, Pediatric Cardiology, published a study in August, 2014: Site of Interstage Care, Resource Utilization, and Interstage Mortality: A Report from the NPC-QIC Registry. This study was completed utilizing data from the National Pediatric Cardiology Quality Improvement Collaborative patient database.

The abstract can be found at the following link: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25107545

What is the background of this study?

o Medical problems and early death remain a problem for children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) during the outpatient “interstage” period between the first (Norwood) and second (Glenn) operations.

o The National Pediatric Cardiology Quality Improvement Collaborative (NPC-QIC) identifies differences in the care of interstage patients in the hopes of learning the best way to care for these children during this sensitive time.

o One difference in care is the place where children receive interstage care. Some are cared for at the surgical site (SS) that performed the Norwood operation. Others are cared for at a non-surgical site (NSS), which could mean a hospital that does not perform the Norwood operation or a private cardiologist. Among those who are followed at a NSS, the distance to the surgical site can vary greatly.

The aims of this study were to answer the following questions:

o Where do HLHS patients receive their interstage care? The surgical site (SS) that performed the Norwood operation, a non-surgical site (NSS), or at a combination?

o How far is the NSS from the SS for those children who are followed at a NSS or at a combination of sites?

o Are there differences in the number of medical problems or deaths associated with the site of interstage care and/or the distance from the surgical center?

How was this study performed?

o The researchers looked back at patients with HLHS entered into the NPC-QIC database over an approximately five-year period (July 2008 to February 2013). The site of each patient’s interstage care was noted as (1) the SS that performed the Norwood procedure, (2) a NSS as described above, or (3) a combination. The distance from the SS to NSS was identified for patients in categories 2 and 3. The number of interstage medical problems, emergency department (ED) visits, readmissions to the hospital, and deaths were identified for each of the three groups.

What were the results of the research?

o Most patients (60%) received their interstage care at the SS. The remaining patients received their care at a NSS (17%) or at a combination of sites (21%).

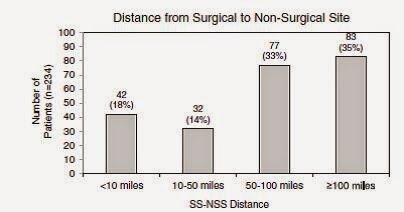

o The patients who received interstage care at a NSS or at a combination of sites were followed at a variety of distances. A large number (68%) of those patients were followed at a distance of 50 miles or greater from the surgical site. The following figures are taken directly from the paper.

o Patients followed at the SS were more likely to have emergency room visits and readmissions. Conversely, patients followed at a NSS or at a combination of sites were more likely to have problems identified with breathing and/or feeding.

o Despite these differences, there were no differences in the rates of death or in the reasons for death among the three groups. Similarly, there was no difference in rates of death based on the SS-to-NSS distance.

o There were 66 patients, approximately 10% of the entire group, who unfortunately did not survive the interstage. It was notable that among those 66 patients, 37 (55%) percent of them died in their home or in an emergency department.

What are the limitations to this study:

o There were several limitations to this study. The main limitations related to the level of detail that was able to be ascertained about these patients.

o The NSS and combination categories were very broad. As noted above, they could be anything ranging from a large medical center that simply does not perform Norwood operations to the office of a single practitioner far from a medical center. This study could not distinguish smaller differences between the two.

o The significance of more breathing and feeding problems identified at the NSS or combination is unclear. It is not known if these patients truly had more problems, or if the fact that these problems were identified reflected more vigilance on the part of the caregivers. Another limitation is that these categories are very broad. Feeding and breathing problems could mean different things to different caregivers. This lack of detail makes a refined analysis somewhat difficult.

What are the takeaway messages considering the results and limitations of this study?

o The site of interstage care does not seem to affect the likelihood of a patient passing away during the interstage period. Similarly, the distance of interstage care from the SS that performed the Norwood does not seem to affect the rate of death.

o More ED visits and readmissions occurred in the SS group, and conversely, more feeding and breathing problems were identified in the NSS and combination groups. As noted above, these differences did not seem to have an effect on death.

o Finally, the mortality rate still remains high at approximately 10%, with many patients dying at home or in an emergency department. This is an important reminder that we still have room to improve interstage care and decrease mortality.

If you missed the first three installments of Research Explained, you can link to them here: https://www.jcchdqi.org/research

Sano vs. BT Shunt

Popularity of the National Pediatric Cardiology Quality Improvement Collaborative's (NPC-QIC) Research Explained is growing. The third installment, brought to you by NPC-QIC's Research Committee, analyzed differences in the Sano and BT shunt used during the Norwood procedure - "Comparison of Shunt Types in the Norwood Procedure for Single-Ventricle Lesions", published in The New England Journal of Medicine in May 2010.

Our families often discuss this same subject, "Sano vs. BT" and are looking forward to your comments regarding this comparison.

Main Finding from this Study

While there has been great improvement in care for patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome and other similar single ventricle lesions that require the Norwood procedure, these patients are still at great risk. When the Norwood procedure is performed there are 2 different ways blood can be supplied to the lungs. A right ventricular-to-pulmonary artery shunt (RVPAS) is placed directly from the right side of the heart to the pulmonary arteries by making a cut in the heart muscle. A modified Blalock-Taussig shunt (MBTS) is placed from an artery that supplies the head and arm to the pulmonary arteries. Each shunt has advantages and disadvantages. The MBTS may cause less blood to flow to the heart muscle through the coronary arteries, but the RVPAS may not allow the pulmonary arteries to grow well and makes a scar on the muscle of the heart. It was not known if one of these shunts were better than the other.

This study describes a comparison of two groups who were randomly assigned to get one shunt type or the other at the time of their Norwood surgery. The authors of this study concluded that in infants undergoing the Norwood procedure, survival without requiring a heart transplant was better at 1 year of age in those receiving a RVPAS than those receiving a MBTS.

About this study

Why is this study important?

This was a very important study because doctors at many different medical centers worked together to find answers to questions that could not be answered by one medical center alone. This is the first time that this type of study was successfully performed in congenital heart surgery, and has helped usher in a new era of cooperation between centers in doing research to improve outcomes in these patients. The number of patients at any single center would not be large enough to be certain that difference are not just based on random events or differences between individual patients, but rather based on an effect of one particular intervention or another. Statistical calculations may be used to correct for individual differences, but can only be used when the groups of patients studied are large. Many other studies have come from the information collected in this study because so many different medical centers worked together to contribute information. This study was also the first fair comparison between shunt types because patients were randomly assigned to a type of shunt. This means that in such a large group, any difference seen between those with the two types of shunts is most likely due to the type of shunt.

In addition, this is a very large group of patients with this heart defect about whom we have a lot of very good baseline information. It will be very valuable to continue to follow them over time, even for their entire lives.

How was this study performed?

This study enrolled patients from 2005-2008 who required the Norwood procedure at 15 medical centers in the United States and Canada. The patients were randomly assigned to one shunt type when they had their Norwood surgery. They were followed after surgery for 12 to 52 months depending on when they entered the study. The main comparison was how many from each group survived to 1 year of age without needing a heart transplant. In addition, they compared how many catheterization procedures each group underwent and the function of the hearts by echocardiogram (echo) for each group.

What were the results of the research?

o 275 patients with MBTS were compared to 274 patients with RVPAS.

o At 1 year of age the RVPAS had more patients alive without needing a heart transplant (74%) than the MBTS group (64%).

When they followed the patients they could for longer than 1 year the difference between the groups disappeared.

At centers that did a lot of Norwood procedures every year there was no difference between shunt types even at 1 year.

o The group getting the RVPAS underwent more catheterization procedures than the MBTS group, mostly to perform interventions to increase the size of the pulmonary arteries.

o At the end of the study there was no difference between shunt groups in the function of their heart by echo.

What are the limitations of this study?

This study went on for many years and patients were enrolled at different times so they were followed for different lengths of time. The main comparisons between groups were made when all patients were about 1 year old. This may not be long enough to know which shunt type is better. Differences at 3 years were also examined and published recently1. These data confirm that differences seen at 1 year did not continue. The number of patients alive without heart transplant was very similar between the two groups (67% for RVPAS vs. 61% for MBTS), even though cardiac function by echo was a little better in the MBTS group and those in the RVPAS group underwent more catheter procedures. A further extension of this trial is ongoing to see what happens at 6 years old.

Differences in many features of patients might be studied, but deciding which are important (other than survival without heart transplant) is difficult. As well, many differences in how patients are treated at different centers can be seen. But since the patients were randomly sorted into groups for comparison based only on the type of shunt they received and not other aspects of care (such as using a certain medication), conclusions about other aspects of care would be very difficult.

What are the takeaway messages considering the results and limitations of this study?

For the 1st year of life, survival without heart transplant is better in those who get a Norwood with RVPAS than those who get a MBTS. After that, there is not a clear advantage to have one shunt over another, but as they continue to collect more information over time, new knowledge may be gained. The group that had RVPAS had smaller pulmonary arteries and underwent more catheterization interventions to try to improve the size of their pulmonary arteries.

1 Newburger JW, Sleeper LA, Frommelt PC, Pearson GD, Mahle WT, Chen S, Dunbar-Masterson C, Mital S, Williams IA, Ghanayem NS, Goldberg CS, Jacobs JP, Krawczeski CD, Lewis AB, Pasquali SK, Pizarro C, Gruber PJ, Atz AM, Khaikin S, Gaynor JW, Ohye RG; Pediatric Heart Network Investigators. Transplantation-free survival and interventions at 3 years in the single ventricle reconstruction trial. Circulation. 2014 May 20;129(20):2013-20.

Many thanks to NPC's Research Committee for continuing to assist parents in understanding research studies that relate to our children with HLHS.

NPC-QIC Research and Publications Committee 2014-2016

Jeff Anderson, Chair, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center

Jean Ballweg, Le Bonheur Children's Hospital

Katie Bates, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia

Michael Bingler, Children's Mercy Hospitals and Clinics-Kansas City

Clifford Cua, Nationwide Children's Hospital

Nancy Halnon, Mattel Children's Hospital UCLA

Garick Hill, Children's Hospital Wisconsin

Colleen Melchiorre, Parent

Patrick O'Leary, Mayo Clinic

Sarah Ortiz, Parent

Matt Oster, Children's Healthcare of Atlanta

David Schidlow, Boston Children's Hospital

Julie Slicker, Children's Hospital Wisconsin

Karen Uzark, University of Michigan Congenital Heart Center

Can the Left Ventricle Be Taught to Grow?

We're excited to share with the HLHS community, a second installment of "Research Explained" courtesy of the National Pediatric Cardiology Quality Improvement Collaborative (NPC-QIC). NPC-QIC's Research and Publication Committee reviewed a study published in November of 2012 - a subject we've covered previously - on Boston Children's Staged Left Ventricular Recruitment (SLVR) for borderline HLHS patients.

We know many of you are interested in reading more about the SLVR program, and some of our Sisters by Heart families have and are currently undergoing SLVR in Boston.

Special thanks to Colleen Melchiorre (Mom to Paul, HLHS) and Dr. David Schidlow for their dedication in bringing us the following "Research Explained."

The Journal of the American College of Cardiology published a study in November 2012: “Staged Left Ventricular Recruitment after Single-Ventricle Palliation in Patients with Borderline Left Heart Hypoplasia.”

The abstract can be found at the following link: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23062531

The NPC-QIC Research and Publication Committee reviewed this article, and a summary of the findings can be found below.

Main Finding from this Study:

Most children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) require three surgeries in the beginning of their lives for survival: the Norwood, Glenn and Fontan surgeries. This result of these surgeries is a heart that only has one pumping chamber (instead of the usual two chambers). For children with HLHS, the right ventricle pumps blood to the body. The process of these surgeries all together is called “single-ventricle palliation”, or SVP. (SVP is the term used in the article, but it might be more familiar to many readers as the “Fontan route”.)

SVP is recommended for most children with HLHS. This is because the left ventricle is too small to help pump blood to the body. In some children, however, the left ventricle is “borderline”, meaning that it might, with the help of multiple surgeries and other procedures designed to promote growth, be able to do the work of pumping blood to the body.

The authors of this paper describe an approach at Boston Children’s Hospital for children with borderline hearts. They show that for certain patients, it is possible to get the left ventricle to grow using a combination of different surgeries and other procedures. Some of the patients who undergo these surgeries and procedures are able to have a “biventricular” circulation, meaning the left ventricle pumps blood only to the body and the right ventricle pumps blood only to the lungs. This is more similar to a healthy normal heart. Perhaps more importantly, this demonstrates that there is the potential for growth of the left ventricle in patients with borderline left heart structures.

About this study:

Why is this study important?

Many children with HLHS who undergo SVP do well. Unfortunately, however, many babies and children do not survive SVP and others have medical problems related to the heart and other organs. This has prompted investigators to explore the possibility of getting the left ventricle to grow in the hope of keeping the left ventricle as the chamber that pumps to the body (this is called a biventricular circulation). These children could (we don’t know yet) have better survival and fewer medical problems than those that undergo SVP.

The authors of this paper describe ways of getting the left ventricle to grow; they call this “staged left-ventricular recruitment”, or SLVR. SLVR procedures include surgeries and catheter-based procedures designed to promote blood flow through the left side of the heart. This includes procedures on the mitral valve, the aortic valve, and within the left ventricle itself. These are all components of the heart that are affected by HLHS, and patients must meet certain qualifications of these components to be a candidate for SLVR.

How was this study performed?

The researchers looked back at patients diagnosed with borderline heart at Boston Children’s Hospital between 1995 and 2010. They compared 34 patients with borderline hearts who underwent traditional SVP, and 34 patients who underwent SLVR. They compared the sizes of different left-sided heart structures. Specifically, they compared the size of the mitral valve, aortic valve, and left ventricle.

What were the results of the research?

At birth, the sizes of the left heart structures were similar in both groups of patients, although the patients in the SLVR group tended to have a slightly larger left ventricle, and patients in the SLVR group were more likely to have had a procedure as a fetus (during the pregnancy) or shortly after birth to open a blocked aortic valve.

Patients in the SLVR group did demonstrate growth in their left-sided heart structures. Specifically, they had a larger mitral valve, aortic valve, and left ventricle than patients who had SVP. The most growth was seen after the Glenn surgery.

12 of the 34 patients in the SLVR group were able to achieve biventricular circulation. 18 of the patients had either Glenn or Fontan type hearts, and 1 underwent transplant. Those with Glenn or Fontan circluation will either continue with SLVR or undergo SVP.

Patients who had a traditional SVP typically had 3 surgeries, whereas patients who underwent SLVR typically had 4 surgeries.

Patients who had a small hole created in the top heart chambers to direct blood flow into the left ventricle were more likely to have growth of left-sided heart structures.

There were 3 deaths (8%) in the SLVR group and 7 deaths (20%) in the SVP group. Although this difference was noted, the number of patients in the study overall was too small to know if that difference was due to the way they were treated.

What are the limitations of this study?

The study looked at a small number of patients. This limits the ability to draw conclusions that can be applied to the general population. Borderline patients encompass a wide range of patients with many different sizes of the left side of the heart.

There may be aspects of the hearts in the SLVR that are different from the SVP group. Patients in the SLVR group were more likely to have a procedure as a fetus or newborn to relieve blockage of the aortic valve. This may mean that there are differences between the two groups despite the size of their left hearts being similar.

This study does not describe how the SVP and SLVR patients are doing clinically, either in the short or long term.

Important questions that could be addressed in the future include

What does the future hold for promoting the left side of the heart to grow?

How are the SLVR patients doing clinically, and what are their long-term outcomes? How do they compare to the SVP patients?

When is the best time to undergo SLVR?

What are the takeaway messages considering the results and limitations of this study?

This study shows promise for promoting growth of the left ventricle in patients with borderline heart. Future study is required to explore the best way to achieve that growth, but this study offers hope.

In order to undergo SLVR, children must meet certain qualifications. It is important to relaize that SVP is recommended for most children with HLHS. In a select group of patients with HLHS - those with a borderlne heart - surgeries and other procedures to encourage the left heart structures to grow are possible. Among such patients, some but not all, will achieve a biventricular circulation.

SLVR includes a variety of surgeries and catheter-based procedures on different parts of the left heart (the mitral valve, aortic valve, and ventricle), and most patients who undergo SLVR will have a Norwood and Glenn procedure prior to achieving a biventricular circulation.

Compared with patients who undergo SVP, patients who undergo SLVR have larger left heart structures, and 12 out of 34 patients who underwent SLVR were able to achieve a biventricular circulation.

More studies are required to understand the best way to promote left heart growth and to understand the short and long-term quality of life for patients with biventricular circulation.

The Bottom Line:

Doctors at Boston Children's Hospital are working to grow the left side of the heart for some children with HLHS. These procedures are still being studied, but they seem to help the left heart grow for some children. In order for your child to qualify, he or she must meet certain criteria. You may wish to talk to your cardiologist about SLVR, and whether your child may be right for it. Dr. Emani (the author of the article reviewed here) can also be contacted at sitaram.emani@cardio.chboston.org.

Factors that Affect Survival of HLHS Infants

Often times, research studies are published in medical journals that relate to our HLHS community. Some of these studies spread rapidly through social media sites and become a topic of conversation amongst HLHS parents.

At the request of NPC-QIC's Parent Leadership Team, their Research and Publication Committee reviewed a recent article that gained quite a bit of traction with HLHS families, nationwide. The study was published in the October, 2013 edition of Circulation: “Prenatal Diagnosis, Birth Location, Surgical Center, and Neonatal Mortality in Infants with Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome.”

NPC-QIC's Research and Publication Committee reviewed the study and provided the following summary for parents, or "Research Explained" as we like to call it.

Key Findings: Prenatal Diagnosis, Birth Location, Surgical Center, and Neonatal Mortality in Infants with Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome

_________

The journal Circulation published a study in October 2013: “Prenatal Diagnosis, Birth Location, Surgical Center, and Neonatal Mortality in Infants with Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome.” http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/early/2013/10/17/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003711.abstract

The NPC-QIC Research and Publication Committee has reviewed this article and a summary of the findings can be found below.

Main Finding from this Study:

The authors of this study concluded that infants with HLHS born closer to a surgical center that performs cardiac surgery on infants have a higher survival rate than infants born far from a surgical center.

About this study:

Why is this study important?

Over the past several devades there has been dramatic improvement in surgical survival in infants born with HLHS. However, ~20% of infants born with HLHS still die within the first months of life. We are constantly looking for ways that we can improve the survival of infants with HLHS, trying to identify improvements we can make in the way we care for these infants. This study attempts to identify risk factors that we might be able to address to improve this survival.

How was this study performed?

The researchers in this study used information from the Texas Birth Defects Registry and identified 463 infants with HLHS born in Texas from 1999-2007. The researchers then looked at where these infants were born, and what the distance and driving travel time was between their birth hospital and the closest surgical hospital that performed stage 1 surgical palliation (Norwood procedure). The researchers then looked for a relationship between this distance and the likelihood of survival of these infants.

What were the results of the research?

Data for a total of 588 infants with HLHS born in Texas between 1999-2007 was available in this Registry.

Several factors were found to be associated with better or worse survival for infants born with HLHS:

The researchers concluded that infants born far from a surgical hospital (more than 90 minutes driving distance away) have worse survival.

Infants with a birth weight <2.5 kg had worse survival.

Infants who had surgery at a surgical hospital who performed more Norwood surgeries had slightly better survival after that surgery.

While prenatal diagnosis was not by itself associated with better or worse survival, prenatal diagnosis is a very important factor related to distance from the surgical hospital; 66% of infants who were born less than 10 minutes from the surgical hospital were diagnosed prenatally as compared to only 13% of the babies born more than 90 minutes from the surgical hospital.

What are the limitations of this study?

Studies that use databases like the Texas Birth Defects Registry are nice because they allow researchers to look at a large number of patients. This is especially helpful when trying to learn about patients with rare problems like HLHS. However, one of the problems with research using databases is that there often is incomplete information about the patients. The following are some of the other things that limit the interpretation of findings from this study.

Survival was better in infants born in the more recent time period (2003-2007) than in the older (1999-2002) period. More infants were diagnosed prenatally in the more recent time period (49% versus 25.5%) and that number has likely continued to increase in recent years.

More infants living more than 90 minutes from the surgical center were Hispanic (30% of mothers born in Mexico) and lived in poverty, suggesting they may have had more limited access to care, including lack of prenatal diagnosis. These socio-demographic factors were not included in the study of factors that may affect survival.

What are the takeaway messages considering the results and limitations of the study?

There are many factors that affect survival of infants born with HLHS. There are some findings from this study that may allow us to improve survival of these infants moving forward.

This study did note worse survival in infants with HLHS born far from surgical hospital. However, there are likely other factors that influence that finding, including the changes in surgical practices over time and socio-economic factors that may influence survival.

Prenatal diagnosis is important because it may reduce mortality if mothers living far away can deliver close to a cardiac surgery center. Prenatal care is also important because we know that infants with HLHS who are born prematurely or with a low birth weight (<2.5kg) have worse survival. We should be doing everything we can to make sure that pregnancies receive adequate prenatal care and appropriate referrals.

We need to continue to understand the relationship between surgical volume (the number of specific procedures that are performed at a surgical hospital) and the survival before and after surgery in infants with complex heart problems like HLHS. Some studies, including this one, have suggested that the more surgeries that are done the better the survival. Collaborative work, like that going on in NPC-QIC will be required to understand the answer to this question.